Executive Summary

Variable annuities with "living benefit" riders that provide retirement income guarantees have been increasingly popular over the past 15 years, and especially in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008. The basic idea of such Guaranteed Living Withdrawal Benefit (GLWB) riders is relatively straightforward: to allow policyowners to remain invested in the markets with a chance for upside, while still having a guaranteed floor (in the form of a benefit base against which withdrawals can occur) that itself may grow over time (e.g., at 5%/year). Yet this potential for the benefit base and associated guaranteed income payments to increase over time itself raises a challenging question for retirees who own annuities with GLWB riders: is it better to begin withdrawals sooner rather than later, or let the guarantees continue to grow and withdraw later instead?

While it seems that many retirees prefer to do the latter and wait - perhaps in no small part due to the confused belief that their cash value is guaranteed to grow at 5%/year, when in truth it's simply their benefit base against which withdrawals can be taken - a deeper analysis reveals that in the end, most retirees with a GLWB rider may do little more than pay a lot in annuity costs to receive a guarantee to just spend their own original contributions and nothing more. The challenge lies in the simple fact that because GLWB riders extract any withdrawals against the policyowner's own cash value first, often the time horizon it takes to actually reach the point where the policyowner has worked through their own cash value and into the insurance company's pocket via the guarantee is actually longer than the client's own life expectancy! In other words, most clients are just receiving their own money back and may literally die before ever seeing a dime of the insurance company's money under a GLWB rider!

Accordingly, it turns out that for those who do have annuities with GLWB riders, the best course of action may actually be not to wait, and instead to tap the annuity for permitted withdrawals as soon as possible (to the maximum allowed under the contract). If the funds being withdrawn aren't needed, they can be moved on a tax-deferred basis via a 1035 exchange, or rolled over to an(other) IRA (in the case of a qualified annuity); nonetheless, the simple fact remains that, with only a few exceptions, the best way to maximize the value of a GLWB rider is to not wait and let it grow at all, as the benefit increases just aren't enough to offset the shortened time window of life expectancy that results from waiting in the first place! Instead, the best course of action is to actually try to deplete the annuity as quickly as possible, in an attempt to reach the point where the policyowner can get a "return" from the insurance company (and not just the policyowner's own original funds) to earn a benefit for the annuity expenses that are being paid all along!

Reviewing A Client’s Annuity With A GLWB Living Benefit Rider

In working with another advisor, I recently came across the following “case study” scenario, which provided an illustrative case of the unique problems that arise with trying to wait on taking withdrawal benefits from a variable annuity with a Guaranteed Living Withdrawal Benefit (GLWB) rider.

In this case, the client was a single female who had deposited $100,000 into a variable annuity (from a major insurance carrier) with a GLWB rider five years ago (in April of 2009, near the trough of the market). She was 65 at the time, and as she now approaches age 70, five years later (and five years into a bull market!), is trying to decide what to do next.

The contract value is now up to $156,586 as of the most recent statement, and is invested in a roughly 60/40 stock/bond portfolio using the company’s (required) moderate growth portfolio (which represents a healthy 9.4% average annual rate of return, albeit over a time horizon that the equity markets were up well over 100% cumulatively). Because the contract has been growing at a healthy pace, the annuity’s GLWB benefit base also recently stepped up to the same $156,586 value. Going forward, the benefit base will grow by 5% of the currently-stepped-up amount, with a guarantee that at the 10-year anniversary (which is another 5 years from now), the benefit base will automatically step up to $200,000 (if it’s not already higher and there have been no withdrawals).

If the client chooses to withdraw, she can receive 6% of the benefit base ($156,586), which would amount to an annual withdrawal of 6% x $156,586 = $9,395; this withdrawal of $9,395/year is guaranteed for life. Under an additional rider, the withdrawal percentage is doubled (to 12%) if the client is confined to a hospital or nursing home.

The cost of the annuity was 1.3% of the cash value for the core mortality and expense fees, plus another 0.90% for the GLWB rider (calculated on the benefit base). The rider fee was recently increased to 1.65% going forward when the GLWB benefit base stepped up to the 5-year anniversary value. This brings the total cost of the annuity to 2.95% (given that the benefit base is currently equal to the cash value), and the cost is further increased by another 0.15% for a hospital/nursing home enhancement benefit. Thus, the total all-in cost for the annuity is 3.10% for its various guarantees.

The client will also still pay the expense ratios for the underlying investment subaccounts (which range from 0.42% to 1.59% depending on the funds chosen). The currently required moderate growth allocation fund has an average expense ratio of approximately 0.80% (bringing the true total cost to approximately 3.90%).

The client indicated that she originally purchased the contract to protect a portion of her retirement assets after the 2008 financial crisis, when she was nervous about the ongoing market volatility and wanted to be certain there was some guarantee underneath her assets. As the markets have recovered, she has not needed to use her guarantee (or take any withdrawals at all), and has only recently begun to consider taking withdrawals to supplement her retirement income. However, as markets have begun to get more volatile, she is once again considering whether it is worthwhile to continue holding onto the annuity and wait before drawing any income, to let the income guarantees accrue even higher.

Evaluating The Value Of A GLWB Living Benefit Rider Guarantee

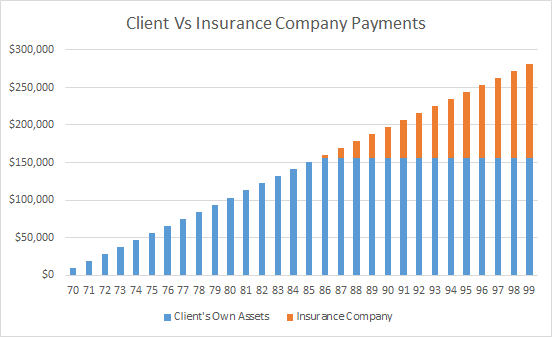

The fundamental caveat of a GLWB rider is that in the initial years, withdrawals are little more than the company returning the client’s own cash value. Thus, for instance, while the client can take $9,395/year from the contract, the client has $156,586 in the contract already, which means for almost 17 years, the client will simply be withdrawing their own money as though there was no guarantee, and it’s only in the 17th year and beyond that the insurance company actually begins to pay out. Notably, as shown in the chart below illustrating cumulative payments out of the annuity, the client will already be age 87 by the time any money actually comes from the insurance company's prospective guarantees!

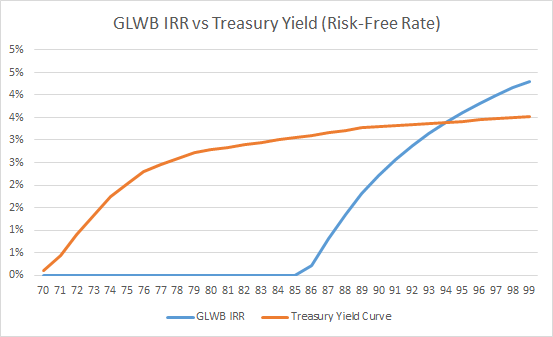

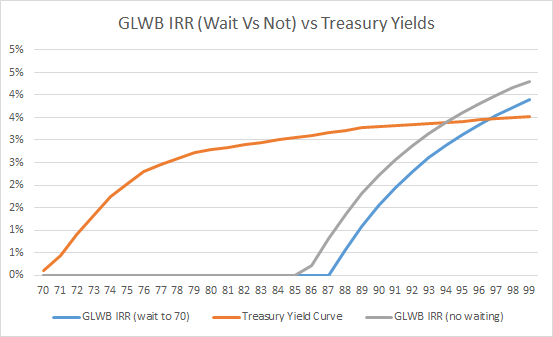

Beyond age 87, the client actually does begin to receive payments from the insurance company – i.e., the actual “benefit” that was being paid for all along the way. However, given that the payments will still only be $9,395/year, the economic value of the guarantee isn’t much initially. After all, it doesn’t take much of an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) on $156,586 to get 18 years’ worth of $9,395/year payments under the guarantee; turning $156,586 into $169,110 of cumulative payments is only an internal rate of return of 0.8%! By contrast, just buying a guaranteed Treasury Bond for 18 years in today’s environment is a yield of almost 3%! The chart below shows the payoff for the internal rate of return on the GLWB, versus just buying Treasuries (as of 4/17/2014) over a similar time horizon. From this perspective, the client doesn’t actually reach a point where the IRR on the GLWB is better than the risk-free rate of a comparable time horizon until the client turns 94!

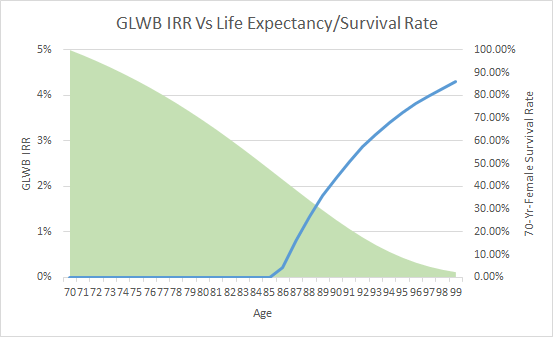

In turn, it’s important to put these time horizons in perspective for a 70-year-old female. Life expectancy (based on Social Security mortality tables) at that point is just under 15 years; the odds the client is even alive by age 87 – which is just the point that the insurance company starts to pay anything other than the client’s own money back to them – is only 38%. It’s not until age 94 that the IRR of the GLWB rider exceeds the risk-free rate of a comparable time horizon; but there's only an 11% survival rate for the client to last that long anyway!

In other words, the odds the client even survives long enough to get payments that exceed the risk-free rate is about 1-in-9, and the odds that the client ever sees anything but their own money returned to them is less than a coin flip! In the majority of cases, all the GLWB rider has actually provided is a guarantee that the client can spend her own money which she already had, at a cost of 3.10%/year (or about 3.90% including the underlying subaccount expense ratios)! Of course, the guarantee also provides an opportunity for upside... though arguably there's not much potential for upside when the client is obligated to remain in a moderate growth balanced portfolio dragging almost 40% in low-return bonds while being slowed by a 3.90% expense ratio headwind!

Waiting For A GLWB Benefit Base To Grow

Notwithstanding the somewhat dismal time horizons for the client to reach her breakeven points, there is often still a desire to keep the GLWB rider in place, and allow the benefit base to continue to grow. After all, in an environment where there is concern that market returns could stumble after an amazing 5-year run, the appeal of a “5% guaranteed growth rate” under the GLWB rider is appealing.

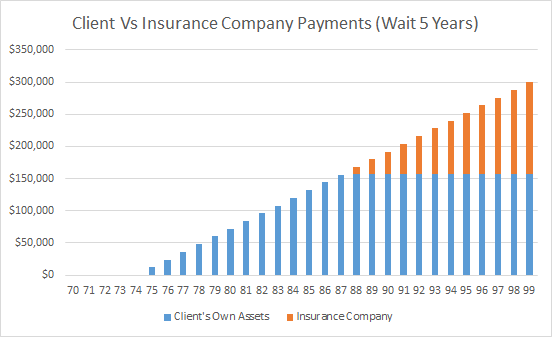

Yet it’s crucial to remember that a GLWB 5% growth rate is not a guaranteed growth rate on the cash value; it is a growth in the GLWB benefit base upon which future guaranteed withdrawals are calculated. Accordingly, if we really want to assess the value of waiting another 5 years until the GLWB benefit base can grow to $200,000, we must reassess the outlook of the prior charts after 5 years, when the guaranteed withdrawals would be $12,000/year (paying what would then be 6% of a benefit base that's up to $200,000). For the time being, we’ll assume market returns really are mediocre (or at least, not enough to beat the 3.90% expense ratio), so there is no further growth in the cash value. Accordingly, the profile of payments (client’s own cash value versus insurance company payments) is shown below.

Notably, the outcome of this chart is that while the insurance company provides larger payments in the later years, now it takes until age 88 to reach the breakeven in the first place (even if we're still "just" withdrawing against the current $156,586 of cash value after another 5 years)! In other words, by waiting to let the GLWB base grow, it actually takes slightly longer to reach the point where the client ever spends anything besides their own money anyway (remember the client only had to wait until age 87 by starting today, per the earlier chart!). And if the portfolio grows at all in the coming years (so the client withdraws against a higher cash value), the insurance company might not have any obligations until the client turns 90+!

Similarly, the next chart below shows the IRR on the payments over the time horizon (compared to Treasuries, and the results by not having waited). As the results show, when accounting for the fact that it takes longer for the payments to reach the crossover point where it’s actually the insurance company’s money being paid at all, the IRR after waiting is actually lower than beginning immediately, and it takes all the way until age 97 before the GLWB guarantee is better than the risk-free rate for a comparable time horizon (and at that point, the odds of survival are less than 5% in the first place!!).

As mentioned earlier, the client’s contract also has a rider that doubles the available withdrawal percentage in the event the client is confined to a hospital or nursing home. Yet in this situation as well, it’s difficult to justify the benefits of waiting. Even at a doubled percentage, the client would be withdrawing “only” $24,000/year at the higher benefit base in the future, and it would still take nearly 7 years for the client just to spend through his/her own money – despite the fact that the average stay in a nursing home is closer to “just” 2.8 years!

Why It Doesn’t Pay To Wait For GLWB Riders

Of course, the outcomes shown above were all assuming that the cash value of the contract does not grow further, and that the GLWB guarantees actually have to be relied upon. Yet ironically, that’s also the point. If the markets are up a little bit, the fundamental results won’t be any different – it may just take even longer for the future GLWB withdrawals to work through the client’s own cash value, making the guarantees even less valuable in an up market. And if the markets are up significantly, the GLWB guarantee will be irrelevant altogether, even while its non-trivial 3.90% all-in cost continues to drag down returns significantly (or a 3.1% expense ratio after accounting for a comparable investment fee in a moderate growth fund outside the annuity)! In other words, if the markets are down the client may never live to see the benefits of the GLWB rider, and if the markets are up, the client may never live to see the benefits of the guarantees, either!

Accordingly, what all of this analysis actually implies is that the best thing the client can do with a GLWB rider is to begin taking withdrawals as early as possible, and not waiting for the GLWB benefit base to grow, for the simple reason that as shown, the value of the guarantee actually is not growing fast enough to offset the shorter time horizon and higher mortality inherent in waiting in the first place. To the extent the money withdrawn under the guarantee isn’t actually needed in the first place, it’s still desirable to take withdrawals sooner rather than later, even if it simply means doing a partial 1035 exchange to a new annuity (to avoid tax consequences), or a partial IRA rollovers (in the case of a qualified annuity). In other words, the client doesn’t have to spend the money, or even pay taxes on it; the goal is just to get it out of the current annuity contract and try to work down to the point where the GLWB actually pays something beyond just the client’s own existing cash value, while the client can reinvest the funds for growth without the unique 3.1% cost drag of the annuity, or the restricted investment choices.

Clearly, the caveat to this sample case study is just that – it’s a case study, an example, an anecdote, and a sample size of one. Nonetheless, it appears that this dynamic is not unique to the particular client/contract involved here; not only do I see this commonly in practice when reviewing existing annuities with GLWB riders, but retirement annuity and actuarial expert Moshe Milevsky has shown in his research that this approach – to tap GLWB riders sooner rather than later – actually should be the standard, and waiting is the unique exception to the rule. In his “Optimal Initiation of a GLWB in a Variable Annuity” study last year, Milevsky and his co-authors found that in general, retirees should be tapping their GLWB annuities as early as their late 50s or early 60s, especially given that many contracts today limit volatility (by requiring asset allocation models), and have ‘modest’ roll-ups. As insurance costs for such riders rise (as they have in recent years), and especially if interest rates (i.e., the risk-free rate on Treasuries rises), it only becomes even more desirable to begin withdrawals earlier rather than later!

As many intuitively note, there is a concern to tapping an annuity with a GLWB rider sooner rather than later – it increases the risk that the contract will be depleted. Yet as Milevsky points out in his research – and the point of this article as well – that’s actually the goal! Until the contract runs out, the client is simply paying annuity guarantee fees to spend their own money. The goal is to get to the insurance company’s money, which means tapping the annuity as soon as possible. As noted earlier, if the funds aren’t needed, they can simply be withdrawn, 1035 exchanged, or rolled over, to minimize the tax consequences; the money doesn't have to be spent, it just has to leave the annuity. The end result and goal is to salvage most/all of the money (invested without that 3.10% expense drag!), and deplete the original annuity to the point that the insurance company pays its benefit, too.

Notwithstanding this research, it is of course still important to analyze the details of any particular annuity contract (or get assistance from a firm that has the expertise to support advisors in this analysis), as no two annuity riders work exactly the same, and there may well be some exceptions to this general rule. In addition, it’s still important to be certain not to withdraw more than the amount permitted to be taken on a dollar-for-dollar basis under the GLWB rider, and surrender charges (if applicable) must be navigated as well (although withdrawals under GLWB riders are generally modest enough to avoid surrender penalties). In addition, many GLWBs will now vary the permitted withdrawal percentage based on certain age bands (e.g., 4% for those under age 60, 5% for those under age 70, 6% for those under age 80, and 7% for those beyond age 80), and clients close to an age band may wish to at least wait until crossing over; thus, for instance, a 69 year old client might not want to withdraw immediately, but instead wait until age 70 and then immediately after his/her begin to withdraw the maximum under the rider. On the other hand, it’s also notable that clients with older annuity contracts (especially pre-2005 that had broader dollar-for-dollar withdrawal provisions) may have additional GLWB strategies available to them.

Nonetheless, the fact remains that for those who did buy annuities with GLWB riders, especially in the past 5 years (where due to the bull market, the cash value is likely to be close to the GLWB’s benefit base), it often does not pay to wait on a GLWB rider to accrue a higher benefit, both because the benefit isn’t rising fast enough to offset the shorter time horizon, and because in the meantime the upside of the contract itself is severely limited given the common expense ratios of today’s GLWB annuities. The situation is further exacerbated by the asset allocation limitations of many of today’s contracts, which essentially force the investor to hold “only” 60% in equities and other risk assets, despite paying annuity expenses for the guarantees on 100% of the portfolio (which is an indirect form of additional annuity cost). Or viewed another way, it may be appealing to purchase a variable annuity for upside growth plus downside protection, but it’s not clear there will be any upside growth in a portfolio within a variable annuity with a GLWB rider dragging 3.1% in annuity costs (plus subaccount expense ratios), in a portfolio that must hold a 40% bond allocation in today’s low return environment. Simply put, the “just” 60% in equities can’t possibly generate a high enough return to overcome the bond drag, and the annuity cost drag, and still have more upside than just investing conservatively and taking withdrawals in the first place.

Thus, the bottom line is simply this: For those who do need the funds anyway (or could use the withdrawals to pair with other strategies like delaying Social Security benefits), tapping a GLWB rider sooner rather than later provides an appealing opportunity to begin to coordinate retirement income strategies. And even for those who do not need the cash flows, it still pays to get the money out of the GLWB rider to the maximum allowable under the terms of the contract, even if it just means the money is moved as tax-efficiently as possible to another investment alternative instead!

Fantastic analysis Michael! I would like to see this same example and analysis completed on Guaranteed Minimum Income Riders as well.

This article seems to disdain these riders, but it fails to take into account two things: 1) sequence of returns risk and 2) investor behavior in down markets. If a client is taking out 6% out of an account (as in this example) and the market crashes like it has done twice the last decade, you will run out of money much earlier. Secondly, clients also often fail to stay fully invested in down markets, and end with lower than average returns. With these riders, the investor usually relies on the underlying guarantees and “rides” the market ups and downs more easily, which leads to better results in the long run.

ilovemiami,

You seem to be missing the point here. Given that in practice these riders have VERY limited upside (given ongoing withdrawals, the high expense ratio, and the asset allocation limitations), the client could make their money last this long or longer by just holding an ultra conservative portfolio and taking distributions directly without the rider. Just stuffing the cash value into a money market and taking 6% of the starting principal will last almost 20 years! And as I showed here, just investing in Treasury Bonds can produce comparable income streams until the client’s early 90s on an also guaranteed basis!

Similarly, starting with a 4% initial withdrawal rate in a balanced portfolio and adjusting the withdrawal each year for inflation also gives far more income over life, and manages the sequence of return risk.

The bottom line is that there just isn’t much actual protection against sequence of return risk from a “guarantee” that ultimately is doing little more than guaranteeing you can spend your own money in most scenarios. It’s intuitively appealing, but as I show with the hard math here, it just doesn’t stand up to the available guaranteed alternatives like just using government bonds, or spending conservatively under a safe withdrawal rate approach.

I will absolutely grant that client psychology is a real issue, and that there IS psychological appeal to these riders. But again, if the alternative is that the client could just SKIP the markets and buy government bonds and end out with similar outcomes, or invest in an ULTRA conservative portfolio and end out with more upside, it’s still hard to make the case for these riders over simply being really really conservative in the first place.

That’s nothing nefarious against the insurance companies; it’s just the simple reality that in the end, the company is investing in and trying to protect against the same market that the client is investing in as well, and there’s no magic pot of money out there that makes the markets “safe” for the insurance company while they’re still “risky” for the client. They’re both exposed to the same market, with all the volatility, sequence of return issues, and other market risks.

– Michael

You show a different perspective which is good for any adviser to consider. I think that most financial planners would agree that IRR is not the best way to evaluate these products. I once did the same calculation for immediate annuities and also discovered that it took many years to recover your money. I took this observational to one of the first “fee only” advisers in the profession and the response I got was that “people are insuring against running out of money”. Whether its a Gwlb, Gilb, or an immediate annuity, its not that another investment strategy may get you to the same result. It’s about insuring ones income against the chance of running out because running out is an unacceptable loss. Many people could be in a better position by not paying for home owners insurance, car insurance, LTC insurance or any other kind of insurance for that matter (with the exception of car insurance because it is mandatory in most states) but people buy it because they want to insure against having an unacceptable loss The reality is these contracts can be manipulated in lots of ways to provide benefits when used and understood correctly. There was a while where you could get withdrawal and death benefit riders at the same time (2007 ish). I met a widow who’s had begun taking withdrawals, the market had tanked, and he died. The wife got back more in death benefit than they had originally put in due to the step ups and was in a great position relative to having had any other diversified portfolio. As usual, it all depends on the clients needs, requirements and preferences.

Great analysis and fantastic response to ilovemiami. He isn’t wrong about investor behavior, but your response is equally, if not more valid than the points he raises. Extending your article’s points even further, would it make sense to show the impact of surrendering the annuity altogether for clients? I would think there must be break-evens on the cost to surrender (there probably is a surrender cost….) versus moving the dollars to a new annuity with much lower M&E, contract, and fund expense ratio costs? Obviously there may be tax implications if the annuity is held outside an IRA, and not 1035’d to another annuity, so that should be taken into account. If I find myself advising a client on what the do with their GMWB, I’d assume they’d want to know 1. should they keep the annuity and start guaranteed withdrawals sooner, 2. surrender the annuity and invest in a portfolio in alignment with their goals, or 3. 1035 the dollars to a lower cost annuity without the GMWB? Do I have this all right?

Many actuaries say that you should never give an insurance company any money you don’t really need to give them. This kind of analysis shows why.

Michael I dont entirely understand your argument…are you saying to avoid living benefits altogether or are you saying if you are using them to turn benefits on immediately and accelerate your principal recovery so you can get into the insurance companies pockets faster? Is it really that big of a secret that the insurance company is paying you back with your own money? I thought that was just common sense. I’ll conceed that these products arent attractive anymore, but there was a time when they were very attractive for clients and made a lot of sense. For instance there were certain products that guaranteed the benefit base would double in 10 years and you could draw 6% off that base for life. From an investment standpoint I cant guarantee my clients portfolio will double in 10 years and I certainly cant prudently recommend they draw down 6% of their portfolio for retirement income. Curious to hear your thoughts….

I’m not sure you fully understand the shell game that is going on with the VA of old you describe…sounds like the Prudential VA from around 2009-highest daily income 6 Plus rider…saying that you can’t guarantee to double the investments over 10 years isn’t at all the point because you are only doubling the future payments (not principal). So a 55 year old buys this thing and at 65 their income stream is doubled…you could do that with near risk-free assets. Actually, you could very prudently recommend they withdraw 6% with a mostly equity portfolio. The Trinity Study shows that a 4% withdrawal rate ADJUSTED FOR INFLATION means that over 30 years of payments, you will have roughly the same payments as 6% not adjusted for inflation. Do the math! Assuming 3% inflation, you actually get a bit over 6% straight-line equivalent. Here is the much bigger point: 96% of the Monte Carlo scenarios led to an ending balance at least as big as the starting amount…only 4% were between $0 and the initial principal investment. Therefore, due to the way the income rider fees are calculated (i.e. as a percentage of the income base instead of the contract value)…for all but the most risk-intolerant clients…and if market history is any guide…you have a 96% chance you are destroying the clients entire principal amount (in opportunity-cost versus coaching them to tolerate higher equity exposure). I can see there being a slight argument for using VAs in very limited circumstances for those with very low risk-tolerance…but it would be a bit like finding that unicorn of a client who has zero risk-tolerance, cannot be taught the benefits of balancing inflation risk with risk of capital loss/volatility, and accepts and understands that their contract value will fluctuate despite the income guarantee. In my experience, VAs are sold if the client doesn’t fully understand what they are buying, the advisor doesn’t understand what they are selling, or both.

Great analysis, Michael, as is your recent post on Fixed & EIAs. I agree entirely regarding today’s riders and having limited upside, but how might your opinion change if there were no investment restrictions? There is still one provider (of course at a slightly higher cost.)

Thank you for doing this important work. You lay it out in a way that can be easily understood!

Great article! Aside from the huge fee drag on the low(er) return portfolio, the annuity payout is very low! 6% of contract value per year for a 70 year old woman? I pulled out my financial calculator and calculated the payment on an IMMEDIATE annuity with the $156,000 contract value, 15 year life expectancy and a 3% discount rate. The annual payment is $13,117. That’s twice as much!

Would it be possible to 1) roll the VA contract into an IRA and invest it in something conservative for a year, then purchase an immediate annuity that would provide her with a much better payout?

I made the mistake of investing in a variable annuity about 3 years ago and your article makes imminent sense. I’m 62 with $127K “protected withdrawal value” in an IRA-based (qualified) Prudential Premier Retirement B Series with guaranteed “highest daily lifetime income.” Which of these two options is best for me? (1.) Keep this product and just start drawing down my 4% benefit and reinvest whatever I don’t need in another IRA or( 2.) Try to do a transfer of the product (actual value $112.5K) to a different IRA or immediate annuity? I understand that since it is an IRA/qualified account, surrender and/or tax fees will be less if I do try to transfer? Thanks for any advice.

Michael, how would you factor in the residual value of the death benefit when making these kinds of decisions?

Michael,

In this article, you said that it might be useful for the owner of a VA with a GLWB to do a partial 1035 exchange of the cash value to a new contract so as to get the cash value in the first contract down, so that the guaranteed withdrawals from the benefit base would represent the insurer’s money rather than the owner’s money. But would not that exchange, being in excess of the free withdrawal rate under the rider trigger the reduction of the benefit base (perhaps on a pro rata basis) and would that not destroy the advantage of the strategy?

Hi Michael – I’m late to the party… Wondering if you’d be able to share the Excel spreadsheets you used for the 5 graphics above? Appreciate you and your informative articles!