Executive Summary

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act brought the biggest changes to both individual and corporate taxes that we've seen in the past 30 years. Included in those changes was IRC Section 199A, which is a new section of the tax code that introduces a 20% deduction on qualified business income (QBI) for the owners of various pass-through business entities (which include S corporations, limited liability companies, partnerships, and sole proprietorships). Fortunately, the QBI deduction will provide big tax breaks for many business-owning clients, but unfortunately, the new deduction is highly complicated, and it may take some time before the IRS can even provide more meaningful guidance on how it will be applied. However, the reality is that the planning opportunities created by IRC Section 199A are tremendous, and practitioners are already eagerly exploring how they can help clients reduce their tax burden through creative strategies around the QBI deduction.

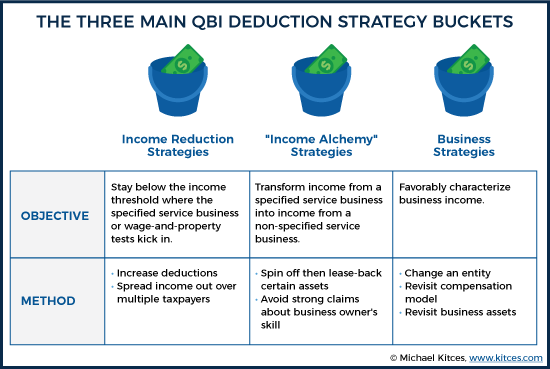

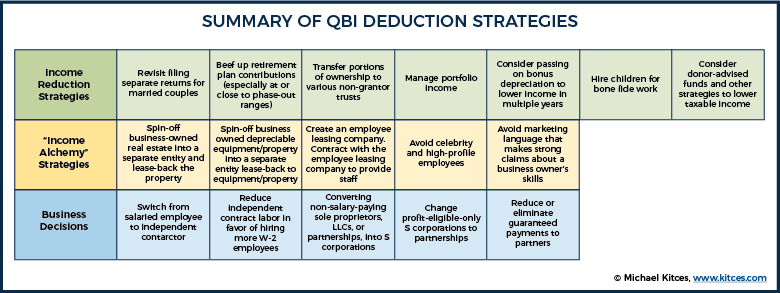

In this guest post, Jeffrey Levine of BluePrint Wealth Alliance shares some of his own QBI deduction strategies and considerations after the TCJA. Broadly speaking, most strategies QBI deduction strategies can be broken into the three buckets, including income reduction strategies to stay below the income threshold where the specified service business or wage-and-property tests kick in, "income alchemy" strategies for transforming income from a specified service business into non-specified service business income, and other business strategies – such as hiring more W-2 employees – which are focused on favorably characterizing business income.

Notably, within each bucket are a wide range of tactics. Business owners who could benefit from income reduction strategies can consider ideas such as planning around retirement contributions, transferring portions of ownership to various non-grantor trusts, and revisiting filing separately as a married couple. Business owners who could benefit from "income alchemy" strategies can consider spinning-off certain assets and leasing them back, creating employee leasing companies, and even avoiding marketing language that makes strong claims about a business owner's skill. And business owners who could benefit from favorably characterizing business income may want to reduce or eliminate guaranteed payments to partners, change profit-eligible-only S corporations to partnerships, or switch from a salaried employee to an independent contractor.

Ultimately, the key point is to acknowledge that IRC Section 199A creates a tremendous number of planning opportunities after the TCJA. New strategies with QBI deduction implications will certainly continue to be developed with time and further guidance from the IRS, but even in the present, financial planners already have enough reason to reach out to business-owning clients and help them reduce their tax liabilities!

QBI Deductions Under The TCJA of 2017

In December 2017, Congress passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, easily making the biggest changes to both individual and corporate taxes in more than 30 years. As part of those changes, Congress created a new section of the tax code, IRC Section 199A, which provides a brand new 20% deduction on “qualified business income” for the owners of various “pass-through business entities” (or really, any business entity that is not a C corporation), including both S corporations, limited liability companies, and partnerships, as well as sole proprietorships.

The good news for advisors is that this deduction, known both as the 199A deduction, or the qualified business income (QBI) deduction, is huge tax break for many of their business-owning clients. The bad news is that the QBI deduction is, without a doubt, one of the most complicated provisions of the new law, and it may be a while before we get some sort of meaningful additional guidance from the IRS itself.

That being said, even with today’s “limited” information, practitioners have been drooling over planning opportunities around the QBI deduction, dreaming up ways to allow business owners to secure the largest possible deductions. Those planning strategies are the primary focus of this article, but in order to plan productively, it’s important to recognize that given the QBI rules as written, business owners will generally fall within one of three categories when it comes to the QBI deduction:

- Business owners below their applicable threshold amount – which is $157,500 of taxable income for all filers except joint filers, and $315,000 for those filing jointly – are able to enjoy a QBI deduction for the lessor of 20% of their qualified business income or 20% of their taxable income. It does not matter what type of business is generating the income, nor is there a need to analyze W-2 wages paid by the business or depreciable assets owned by the business. The QBI deduction is what it is.

- Business owners over their applicable threshold who derive their income from a “specified service” business (i.e., some specialized trade or service business) – which includes doctors, lawyers, CPAs, financial advisors, athletes, musicians and any business in which the principal asset of the business is the skill or reputation of one or more of its employees – will have their QBI deduction phased out. The phase out range is $50,000 for all filers except joint filers, and $100,000 for those filing jointly. Once a business owner’s taxable income exceeds the upper range of their phase-out threshold ($207,500 for individuals, and $415,000 for married filing jointly), they cannot claim a QBI deduction for income generated from a specialized trade or service business. Period. End of story. “Do not pass go, do not collect $200.”

- Business owners over their applicable threshold who derive their income from a business that is not a specialized trade or service business may also have their QBI deduction at least partially phased out, but the full deduction may be “saved” based on how much they pay in W-2 wages and/or how much depreciable property they have in the business. Business owners with qualified business income from non-specified- service businesses whose taxable income exceeds the upper range of their phase-out threshold can still take a QBI deduction equal to or less than the greater of:

- 50% of the W-2 wages paid by the business generating the qualified business income, OR

- 25% of the W-2 wages paid by the business generating the qualified business income, plus 2.5% of the unadjusted basis of depreciable property owned by the business.

A careful analysis of the rules above will lead one to realize that, when it comes to maximizing a business owner’s opportunity for a QBI deduction, strategies will fall into one of three main buckets:

- Income reduction strategies, such as trying to lower taxable income by increasing deductions or spreading out the income over multiple taxpayers, in order to stay below the income threshold where the specified service business or wage-and-property tests kick in.

- “Income alchemy” strategies, where we try and transform income derived from a specified service business into income derived from a company that is not a specified service business, to avoid the phaseout (for those over the income threshold).

- Business strategies, such as changing an entity, revisiting compensation models, and revisiting business assets, in order to more favorably characterize business income in the first place.

Some of the strategies to be discussed to potentially maximize a business owner’s QBI deduction are pretty simple and can likely be implemented with little to no effort. Other strategies, however, may require the assistance of a full complement of experts, including lawyers, CPAs, and business consultants. It’s important to remember though, that these strategies are generally only necessary for business owners with qualified business income whose taxable income exceeds their applicable threshold.

We’re still in the early days, and more strategies and ideas are likely to come (and the IRS and Treasury may or may not try to limit some of them when anticipated Regulations are released later this year), but here’s synopsis of some of the best strategies that are already being discussed…

Relook at Filing Separate Returns for Married Couples

The tax code has long limited married couples filing separate returns from taking advantage of a number of tax breaks, either by barring those tax breaks entirely under the Married Filing Separately status, or phasing them out at very modest income thresholds. As a result, in the past, it’s rarely been a tax-efficient move for married couples to file separate returns, except in highly unusual circumstances. That will likely still be the case for most married couples, but the creation of the QBI deduction does tilt the balance somewhat for some couples.

The primary reason is that under Section 199A, “the term ‘threshold amount’ means $157,500 (200 percent of such amount in the case of a joint return).” Thus, married couples filing separate returns find themselves in the unusual position of each actually getting the same benefit as single filers (and even those filing as head of household or qualifying widow(er)), rather than being relegated to a less favorable threshold.

In situations where one spouse’s income would be eligible for the QBI deduction but no such deduction can be received because the other spouse’s income pushes the couple over the higher $315,000 threshold amount for joint filers, it’s worth exploring if filing separate returns could lower the household’s combined tax bill. Again, this is not likely to be the case for most couples, due to the other impacts associated with filing separately, but it’s an option that must be at least considered when the QBI deduction is available for one member of the couple but phased out fully or at least in part by the other spouse’s income.

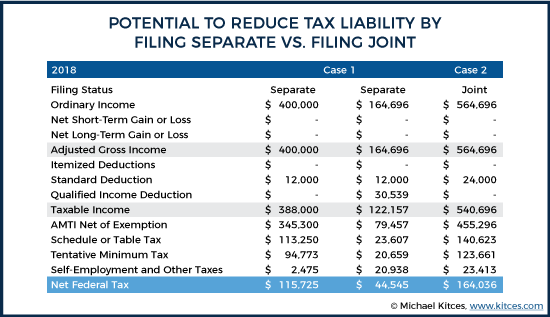

Example 1a: Bill and Sally are married and have always filed a joint return. Bill is a W-2 employee and makes a $400,000 salary as a corporate executive. Sally is a sole-proprietor CPA (a specified service business) whose business is estimated to generate a net business profit of $175,000. Together, Bill and Sally’s taxable income is well over the $415,000 upper limit of the phase-out for the QBI deduction for joint filers. Thus, Bill and Sally are unable to claim any amount of QBI deduction for Sally’s otherwise-eligible business income. Assuming no other deductions or credits, Bill and Sally would have a total 2018 federal income tax liability (including Sally’s self-employment tax) of $164,036.

What if, however, instead of filing a joint return, Billy and Sally chose to file separate returns? I used BNA Income Tax Planner, of one my favorite tools, to crunch the numbers, and as it turns out, given the above fact pattern, this typically unfavorable move would actually produce a favorable result!

Example 1b. Continuing the prior example but using the Married Filing Separately status, instead of jointly, not much changes for Bill, other than switching over to the married-filing-separate brackets and getting a $12,000 standard deduction (half that of those filing a joint return). Ultimately, his $400,000 salary results in a standalone $115,725 federal income tax liability for 2018.

Things do change rather significantly for Sally though. Now, “unshackled” from Bill’s high salary (talk about a nice problem), Sally is able to reap the benefit of a substantial QBI deduction. After accounting for self-employment tax and her own standard deduction, Sally would be eligible for a $30,539 QBI deduction. Her resulting taxable income of $122,157 leaves her with a tax bill of $44,545.

[Tweet "Due to the new QBI deduction, married, business-owning couples may want to file separately!"]

Added together, Bill and Sally have to pay a combined tax bill of $160,270 in Example 1b, which is nearly $3,800 in tax savings over Example 1a… just for changing their filing status! If Bill and Sally use a professional tax preparer to file their return, the additional cost of filing a second return (since they are now each filing separately, by definition) may eat into that savings a little bit, but they would no doubt still wind up in the green. And from a practical perspective, many professional tax software packages will automatically analyze the decision to file a joint return vs. filing separate returns. In such cases, the cost to file the added return may be minimal or even non-existent.

Of course, the one major complication of this strategy is the need to file two tax returns instead of one in the first place. But that’s actually a lot less intensive than other approaches we’ll explore later in this article!

Note: This strategy may not be applicable to clients who live in community property states (Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington and Wisconsin – Alaska also allows taxpayers to opt-in to community property), as “community income,” which typically includes salaries, wages, and other pay for services performed, must generally be apportioned equally between spouses, regardless of filing status.

Revisit Entity Selection

Beyond whether couples should file separately, one of the more common questions advisors are likely to face this year is whether a business owner should revisit their entity structure altogether. Indeed, there are scenarios one can conjure up where a business owner can be starting with any given entity structure, and end up with just about any other entity structure making sense.

Fortunately, the fact that the QBI deduction is potentially available for any business that is not a C corporation, it is not necessary to form a “pass-through” entity like an S corporation, LLC, or partnership, or in order to claim the QBI deduction. Sole proprietorships are fully eligible as well, without literally having a “pass-through business entity”.

Nonetheless, there will be many other situations where it’s necessary to take a fresh look at business entity structure, both for employees who may want to become a pass-through entity (or at least an independent contractor) to be eligible for the deduction, and existing business entities that may want to convert to other types in order to better maximize the QBI deduction.

Switching From Salaried Employee to Independent Contractor

In some instances, it may pay for an employee to look to restructure their “employment” with an employer, and make the move to go to an independent contractor model instead. From the employees perspective, such a move could offer substantial tax savings thanks to the QBI deduction.

Example 2: Clarence is a plumber and earns a salary of $150,000 per year from his employment with ABC Plumbers. That $150,000 is fully subject to federal income tax. Alternatively, suppose Clarence goes to his employer and together, they agree to terminate Clarence as an employee and to contract Clarence directly, as a sole proprietor, for $160,000 annually. The net result to each, after account for the higher compensation but the shift in employment taxes (i.e. FICA and FUTA) is roughly the same. Now, however, Clarence could potentially receive a substantial QBI deduction. As an added bonus, Clarence would now be able to deduct items such as the cost of uniforms, equipment, mileage between work sites, etc., as business expenses… which is especially appealing since such unreimbursed business expenses are no longer even deductible as they were in the past, thanks to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act!.

Of course, it’s important to adjust for any other employee benefits that employees may be receiving, such as employer-paid health insurance or employer retirement plan matching contributions, that are no longer available as an independent contractor. Nonetheless, from a tax perspective, the shift from employee to independent contractor status may be appealing for many, especially those who are not over the specified service business income threshold (where, depending on the nature of the business, the QBI deduction may be phased out anyway).

Switching “Employees” From Independent Contractors to Salaried Employees

While some employees may want to switch from salaried employee to independent contractor, the flip-side of the coin for the business owner is that it may be more appealing to switch “employees” from independent contractors to actual employees that work in-house – specifically for those who are high-income business owners that operate a non-specialized trade or service business but are subject to the high-income wage-and-property tests.

Example 3: Alicia runs a successful widget-making company, and earns $600,000. With $600,000 of business profits, Alicia’s potential 20%-of-QBI deduction could be as much as $120,000. Unfortunately, however, Alicia designed the widgets several years ago, and has utilized outside labor to both manufacture and distribute her product. She has no depreciable business property, and no W-2 wages paid. Thus, even though Alicia does not operate a specialize trade or service business, she is presently unable to claim any QBI deduction, as she’s limited to either 50% of W-2 wages, or 25% of W-2 wages plus 2.5% of her depreciable property… all of which is $0!

Suppose, however, that in 2018, Alicia paid $325,000 to independent contractors for their distribution services. Here, a “simple” change could have dramatic tax savings for Alicia. Alicia could decide to bring her distribution in-house, and hire the sales personnel as full-time employees. Consider what would happen if she hired three full-time salespersons at a salary of $85,000 each ($255,000 total). After factoring in employment taxes, benefits, etc., her total outlay for sales might be about the same, but now she’d have a business that paid $255,000 of wages. Absent other factors, Alicia’s QBI deduction of $120,000 would be allowed because it is less than $127,500 (which is 50% of the total wages paid). The end result for Alicia is a similar net payment to her contractors/employees, but a personal federal income tax savings of roughly $40,000!

Of course, the irony of this situation is that, as noted earlier, the “good” news for the business owner that turns their independent contractors into employees may be “bad” news for the employees themselves, who would no longer be able to claim their own QBI deduction on their independent contractor incomes once they become full-time employees!

Converting Non-Salary-Paying Sole Proprietors, LLCs, Or Partnerships, into S Corporation

Under the existing tax law, certain types of business owners are not eligible to pay themselves a salary. This includes business owners operating as a sole proprietorship, as well as owners of partnerships and LLCs that are taxed as partnerships.

In many cases, the lack of an ability for business owners to pay themselves a salary – as opposed to having self-employment income – is not going to be a big deal… after all, the dollars go to the business owner either way. But for some, this restriction could have huge implications in light of the QBI deduction.

To determine if this is something that “could have huge implications” for a business owner, consider three questions:

- Is the entity one that restricts the business owner from paying themselves a salary?

- Is the business not a specialized trade or service business?

- Does the business owner have taxable income in excess of their threshold amount (when considering all income on their personal tax return)?

If the answer to all three of these questions is yes, the business owner is a prime candidate for considering a change in entity to an S corporation. The following example clearly illustrates the relative advantage an S corporation may have for a business owner if the fact pattern above lines up.

Example 4: Kelly is the owner of a successful sole proprietorship that is NOT a specified service business, but nonetheless has no W-2 employees (just some independent contractors) or depreciable property. In 2018, Kelly is projected to have net business profits of $750,000. Despite the fact that Kelly’s business is not a specified service business, she will be unable to claim any QBI deduction for 2018 because her income is too high, and her QBI deduction isn’t “saved” by (25% to 50% of) W-2 wages paid or (2.5% of) depreciable property.

Suppose, however, that Kelly changes her business entity type to an S corporation, and pays herself a $300,000 salary. Now, after paying Kelly her salary, Kelly’s business will have a net profit of $450,000. Her potential QBI deduction here is $90,000, and now, even though her total income is still $750,000 and well above the upper-limit of the QBI deduction phase-out range, her deduction is “saved”, as the limit of 50%-of- W-2 wages paid by her business would leave enough room to claim the $90,000 QBI deduction… even though the W-2 wages were simply paid to herself! And in addition, she may even save a small amount of FICA Medicare taxes as well (on the $450,000 of S corporation profits not taxed as employment income!).

Keen observers will likely notice that while the above example with Kelly produces a dramatically better outcome than had she left her business organized as a sole proprietorship, it’s not the optimal result. Kelly paid herself $300,000 of salary. Half of that salary – the amount she can use to “save” her QBI deduction is $150,000 – but Kelly only had a potential QBI deduction of $90,000. Thus, had she paid herself a little bit less, and had a correspondingly slightly larger net profit (qualified business income), her QBI deduction could have been even higher!

Outside of some guess and check work, is there some simple way to figure out what that optimal salary level is to avoid “wasting” any salary and to produce the largest possible QBI deduction? As it turns out, there is. In a May 3 article on posted to Leimberg Information Services, well known attorney Steve Oshins discussed what he called “The Magical 28.57% W-2 Formula.” In the article, Oshins explains how “the ideal sweet spot for percentage of W-2 wages paid versus overall business income is 28.57%.” Certainly, using this formula would seem to be a lot better than the guess and check method many would otherwise likely employ!

To see the formula at work, let’s revisit Kelly’s business, which has total business income of $750,000 prior to paying her a salary. Multiplying $750,000 by 28.57% gives us a target salary of $214,275. That would leave Kelly with business profits of $535,725. 20% of that amount, or $107,145 nicely matches up to half of Kelly’s salary $107,138 (note: there’s a small tracking error here due to the fact that the 28.57% figure has been rounded to the nearest hundredth percent).

Also, it’s important to bear in mind that while Kelly’s business in the above example was initially structured as a sole proprietorship, business owners with other entities taxed as a partnership (e.g., LLCs, or partnership entities) could encounter the same problems, and benefit from the same opportunity, as the W-2 wage requirement necessitates actual W-2 wages, not “just” guaranteed payments to the business owners.

Converting From S Corporation to LLC Or Partnership

A change from an S corporation to a partnership (or LLC taxed as a partnership) could result in a lower tax bill for a business owner, particularly if they already pay themselves a salary from their S corporation that is close to or above the maximum amount of earnings subject to Social Security tax each year, which for 2018 is $128,400.

The reason is that while salary paid to the owner of an S corporation for services rendered is not considered qualified business income and thus, is not eligible for the QBI deduction… Partnership income – other than guaranteed payments (discussed further below) – is considered qualified business income and is therefore eligible for the QBI deduction.

Example 5: Paul is the sole owner and employee of an S corporation that generates $110,000 of gross income. He pays himself a $100,000 salary annually, deemed reasonable by his CPA, and takes the remaining $10,000 of business profits.

In the past, structuring his business in this manner saved Paul about $1,500 in employment taxes annually (FICA taxes not paid on the last $10,000). With the advent of the new QBI deduction, Paul will begin receiving an addition $2,000 QBI deduction based on his $10,000 of profits.

If Paul were to change structure of his entity such that he was taxed as a partnership, though, his entire $120,000 of income would be eligible for the QBI deduction, giving him a total QBI deduction of $24,000, while his self-employment taxes would only increase by ~$1,500 (since the bulk of his income was already salary subject to FICA taxes).

The net result in the above example is that the additional $22,000 QBI deduction for Paul will likely result in far more tax savings greater than the additional ~1,500 in employment taxes he’d have to pay in this scenario. For instance, even if Paul is in “just” the new 22% tax bracket, the QBI deduction would be an additional $4,400 of tax savings.

One reaction to this strategy might be to simply wonder “Well, why doesn’t Paul just pay himself a lot lower salary from his S corporation?” Lowering his salary may be possible, but there’s a risk: for years, business owners have used S corporations as a way to minimize exposure to employment taxes, pushing down their salaries as much as possible in order to make less of their income subject to employment taxes, and thus not surprisingly, this has been a hot-button issue with the IRS for some time. The new Section 199A is likely only to increase the gamesmanship here though, as not only are S corporation profits not subject to employment taxes, but they are also potentially eligible for a QBI deduction, whereas the salary an S corporation owner pays to themselves is not! Which means while the temptation to manipulate S corporation salary is higher, so too is the likely scrutiny from the IRS.

In other words, if this was an area of concern for the IRS before, one can only imagine the added attention it will receive in years to come when salary manipulation is both a FICA tax issue and a potential QBI deduction abuse. Whereas while converting away from an S corporation to an LLC or partnership would take the FICA tax strategy off the table, for those already at or near the Social Security wage base, the FICA cost is minimal… for a QBI deduction that would no longer have a red-flag for the IRS (as there is no such thing as business owner salary in an LLC or partnership taxed as such, and therefore nothing for the IRS to challenge!).

Converting From S Corporation to C Corporation

The purpose of this article is to discuss the various ways in which the QBI deduction can be maximized. C corporations are ineligible for the deduction, and thus, this particular approach is not addressed in depth here. However, in light of the C Corporation’s new top 21% tax rate, business-owning clients need to make sure that they re-evaluate this option. This would be particularly true if the individual tax rates and QBI deduction are not extended beyond 2025 – when they are currently scheduled to sunset – while the permanent lower corporate tax rates persist.

Revisiting Retirement Plans To Maximize QBI Deductions

Setting up retirement plans for small business owners to help minimize taxes is nothing new for advisors. In fact, it’s long been one of the easiest and most effective ways of reducing a business owner’s taxable income. The flexibility of the business owner and his/her level of control provides ample room for planning here, such as the selection of the best type of plan, the ability to employ family members (for legitimate services rendered) and include them in the plan, etc.

Many business owners though, for one reason or another, choose not to take advantage of all that retirement plans have to offer. If, however, the key objective of the retirement plan is to help the business owners pay tax when rates are lowest – and it often is – then there should be no doubt that deductible/excludable contributions to a tax-deferred plan can make more sense than ever in light of the QBI deduction.

Example 6: Alex and Charlene are married and own a partnership that generates $439,000 adjusted gross income, all of which is derived from a specified service business. After claiming the standard deduction, Alex and Charlene would find their QBI deduction is phased down to $0 given their income (which is above the phaseout threshold for a specified service business), which would result in a 2018 Federal income tax bill (ignoring self-employment taxes) of $96,629.

Suppose, however, that Alex and Charlene create a 401(k) plan and they get $50,000 of contributions into each of their accounts. As a result, they are able to decrease their AGI by $100,000. How much does this lower their total tax bill? Well, as it turns out, quite a bit more than one might expect! The $100,000 of cumulative retirement account contributions not only reduce Alex and Charlene’s AGI by an equivalent amount, but they also reduce taxable income enough to claim a substantial QBI deduction.

Amazingly, assuming that Alex and Charlene claim the standard deduction and the maximum QBI deduction for which their eligible (which is now $63,000!), their 2018 tax liability would be reduced to $49,059. That’s a whopping $47,570 decrease in taxes (a combination of tax deferral for the 401(k) contribution itself, and the benefit of the QBI deduction), meaning that the last $100,000 of income Alex and Charlene earned through the QBI phaseout zone was subject to a marginal rate of 47.57%! It’s hard to imagine how Alex and Charlene wouldn’t come out ahead when their retirement plan contributions are saving dollars at a 47.57% marginal tax rate, and the maximum top tax bracket on their future withdrawals is only 37% under current law! Which means it would take a substantial increase in the current rates, or other dramatic changes to the code (which admittedly is within the realm of possibility, but rather unlikely) for the retirement contribution to turn out badly!

Ultimately, the key point of this strategy is to reduce the income of a specified service business owner below at least the upper end of the phaseout threshold (where the QBI deduction is lost entirely), and ideally low enough to claim the full QBI deduction (which means taxable income below $157,500 for individuals, or $315,000 for married couples). However, given the availability of not just 401(k) or other defined contribution plans, but the opportunity to layer cash balance and other defined benefit plans on top, the strategy remains relevant for even rather high-income small business owners (at least those who have the financial wherewithal to stuff away hundreds of thousands of dollars each year into tax-deductible retirement plans in the first place!).

Shifting Business-Owned Real Estate to New Entities and Pay Rent

Many businesses own the real estate out of which they operate. If this is the case for a higher-earning business owner, then there is an obvious way of converting some of their specified service business income into income from a business that may qualify for a QBI deduction. In short, the business owner can create a new entity, transfer the real estate into that entity, and then lease that real estate back to the original business. The original business’s profits, which are not eligible for the QBI deduction (assuming the business owner’s taxable income exceeds their applicable threshold), will decrease, and profits can be shifted to the new real estate company, which could potentially qualify for at least a partial QBI deduction.

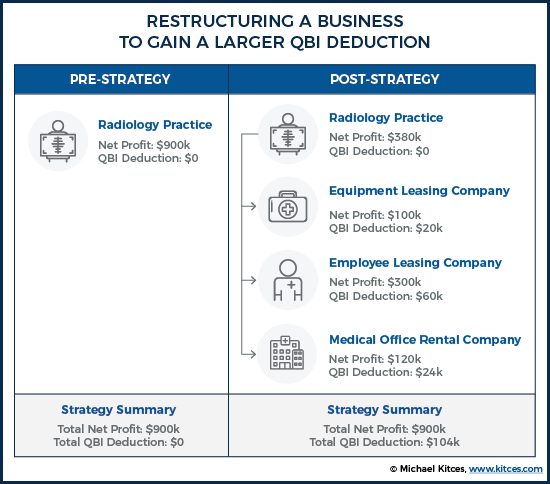

Example 7: Susanne is a doctor, and is the sole owner of a radiology practice organized as an LLC. Her income from the practice – which falls under the specified service business umbrella – is $900,000 per year. Thus, Susanne is currently ineligible for any QBI deduction. Several years ago, the LLC purchased the medical offices out of which the radiology practice operates for $2,000,000. The upkeep on the office space, the depreciation on the property, and other expenses, currently reduce the net profit of the LLC by about $100,000 per year, but the property provides little else in the way of tax benefit for Susanne.

One option to consider in case like this would be to spin off the medical office building into a separate LLC, or other business structure, and have the medical practice rent space in the building. Those rent payments would be deductible for the medical practice, and taxable income for the new business… except the profit in the new business may be eligible for the QBI deduction!

For instance, suppose that after spinning the medical office off into its own entity, the radiology practice leases the office space at the rate of $220,000 per year. The net result of such a transaction would be that the radiology practice’s net income would be reduced $120,000 ($220,000 rental expense - $100,000 prior expenses “lost” = $120,000). The real estate entity, on the other hand, would now have a profit of $120,000 – a net shift of zero – but the real estate’s income could qualify for the QBI deduction! Thus, the final result is an equivalent amount of business income, but a $24,000 QBI deduction for Susanne on her personal return that, at her tax rate, would save her nearly $9,000 in federal income taxes annually.

While this may be one of the more “basic” approaches to helping business owners secure a QBI deduction, there are still a number of issues which planners must address. For instance, in the example above, Susanne’s taxable income is well above $415,000. Thus, the QBI deduction she’d be eligible for on the profits from her new real estate business is potentially limited. The unadjusted basis of the property is worth $2,000,000, so absent other factors, given Susanne’s income, the maximum amount of her QBI deduction would be $50,000 ($2,000,000 unadjusted basis x 2.5% = $50,000). Today, that’s more than enough to “cover” the $24,000 QBI deduction calculated above, but as time goes on and rental payments increase, that may not always be the case. When that time comes, further planning might be helpful. For instance, Susanne might consider hiring a maintenance worker to perform work that today is outsourced, such as basic landscaping, maintenance, etc. Converting that expense from an independent contractor expense to a W-2 expense would increase the eligibility cap on Susanne’s potential QBI deduction by 25% of the wages paid.

Another area to which planners must pay attention is the likely situation where the owners of the specified service business and the owners of the real estate are the same, or substantially the same. In such a case, the adversarial relationship that typically exists when a lessee and a lessor negotiate a lease agreement is not present. Normally, a lessee is looking to pay as little rent as possible, whereas a lessor is interested in getting the highest rent possible to provide a return on his or her investment. Thus, any agreement reached is likely to reflect a fair market value for the property and be considered an arm’s-length transaction. The exact opposite is true in situations where the business owner owns both sides of the transaction, which can raise concerns for the IRS.

For instance, consider in the above example what would have happened if Susanne leased the medical offices to her radiology practice at a rate of $1MM per year. The result would be a medical practice that has no profits, and a real estate business that has a profit of $900,000. Thus Susanne would have converted all of her non-QBI-deduction-eligible income into income that could, subject to W-2 and depreciable property limitations, be eligible for the deduction… except that is not going to fly with the IRS… ever, because $1MM/year is not remotely close to a reasonable market rental rate. That type of non-arms-length, sham transaction would be unwound by the IRS quicker than you can say “QBI.” Therefore, it is essential for planners to make sure that the lease payments their business owner clients make between related businesses are made at a bona fide fair market value. Consulting knowledgeable real estate professionals as to an appropriate fair market rate, and maintaining copies documenting those estimates, could be key in any potential dispute with the IRS down the road.

Shift Other Business-Owned Assets to Other Entities and Lease Them Back

For some business owners, there’s the potential to continue to push the boundary even further on shifting depreciable property out of a business, and then leasing it back to the original business entity.

Example 7b. Continuing the earlier example of Susanne and the radiology practice above, suppose the practice also owns an MRI machine, several X-Ray machines, and a variety of other depreciable medical equipment as well, with an unadjusted basis of $2,500,000 (note: an MRI machine alone can range from about $1MM to $3MM, so this is not unreasonable!). This equipment could be spun off into yet another business, and the radiology practice could lease back the equipment.

The mechanics and the potential tax benefits of this move are essentially the same as when real estate is moved into a separate entity. When it comes to the QBI deduction, depreciable business property is depreciable business property. The 2.5% limitation is not impacted by the type of depreciable property or the length of time over which it will be depreciated.

So let’s suppose that Susanne goes through with this move and leases back the imaging machines and other medical equipment at a rate of $350,000 per year and that, after accounting for depreciation and other expenses, produces a profit of $100,000 in the new leasing company, and further decreases the profit of the medical practice by another $100,000 annually. The result is another $20,000 of QBI deduction for Susanne, saving her almost another $7,500 in income taxes annually.

Of course, the limitation to this strategy is that not all small businesses have substantial (or much or any) depreciable property to spin off into other entities in the first place… and at some point, any/all depreciable property that could be spun off will have been. So that’s it, right? Maybe not…

If You Can’t Lease Equipment, Lease People With An Employee Leasing Company?

Many specified service businesses are labor intensive, but may not necessarily require a great deal of depreciable property. Law firms, accounting firms, and financial advisory practices, are all good example of this. Outside of some office furniture and some computers, these businesses can generate substantial profits, without ever owning any significant amount of depreciable property. They do, however, often employ a great number of people, and spend substantial amounts on human capital.

To that end, the language in Section 199A leaves the door open to the possibility of creating an employee leasing company, and leasing back one’s employees from that company. Some practitioners believe this to be a gaping hole in the rules, while other practitioners are a little more cautious at this time. Indeed, the AICPA included a question related to employee leasing in its February 21, 2018 letter to the IRS requesting clarification on several QBI-deduction-related issues (though to be fair, the issue it raised was slightly different than the one presented here).

Example 7c. Continuing our earlier and ongoing example, let’s suppose that Susanne, our radiology practice owner, medical office rental property business owner, and medical equipment leasing company owner, is comfortable pushing the boundaries a bit. Further suppose that her radiology practice currently employs a variety of persons unrelated to the actual delivery of patient services. This might include medical records workers, billing personnel, and collections staff, just to name a few. All told, these workers are paid an aggregate of $1MM of W-2 wages and benefits per year.

What if Susanne decided that, instead of hiring these employees directly, she would create yet another business, an employee leasing company, commonly known as a Professional Employer Organization (PEO), and would lease those employees directly from that company? Such business have long existed, and are used by business owners for a variety of reasons, including mitigating legal issues arising from employment matters, and to outsource various functions, such as payroll and employee benefits. These businesses have real functions, and have real risk, so they aren’t doing it for free! They’re trying to make a profit, just like any other business. Thus, while a PEO might only pay its leased employee $100,000 annual salary, it might charge the lessee $130,000 (a 30% markup) to rent that employee. Except that for a business owner trying to shift “profits” out of a specified service business, that’s actually good news!

Consider then, that after establishing her new employee leasing company, Susanne leases employees from that company to perform the same tasks that were previously handled by “in-house” staff. Furthermore, let’s imagine that those employees are paid the same wages and receive identical benefits as before, but now receive them through the leasing company. Finally, suppose that Susanne’s radiology practice leases those employees from the PEO at a rate of $1.3MM annually (with the same 30% PEO markup). The $300,000 of profit would vanish from Susanne’s not-QBI-eligible medical business income, and would appear, at least on the surface, to qualify for the QBI deduction in her employee leasing business, producing yet another $60,000 of deductions for Susanne, and saving her well over another $20,000 in federal income taxes!

Notably, the cumulative result of such income shifting practices from a specified service business can really add up. Taken together, Susanne’s decisions to go from radiology practice owner to multi-business-owning mogul result in over $100,000 of deductions annually, allowing her to keep more than $35,000 in her pocket annually instead of Uncle Sam’s. Of course, Susanne now has four businesses, which will no doubt add complexity to her life. Chances are, clients like Susanne won’t be dealing with that themselves, so any additional costs of these decisions, such as increased accounting and tax preparation costs, should be carefully considered. Though $35,000 of cumulative tax savings provides a substantial amount of room for some additional accounting and bookkeeping service costs!

[Tweet "QBI deduction strategies may be well worth the added bookkeeping costs!"]

Reduce Partnership Or LLC Guaranteed Payments to Partners Where Possible

One of the easiest ways that an advisor can help certain business owners increase their QBI deduction is by helping them revisit their partnership arrangements. The issue is that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act specifically excludes guaranteed payments to partners from being treated as qualified business income, which renders those “business income” dollars ineligible to qualify for the deduction. Accordingly, a relatively “simple” revision of the partnership agreement, eliminating what may not really be “necessary” guaranteed payments, could result in a substantial tax savings.

Example 8: Sean and Harry formed a partnership, SH Services, two years ago. Sean owns 70% of SH Services, and Harry owns the remaining 30%. Their partnership agreement calls for each of them to receive guaranteed payments of $100,000 per year, with additional partnership profits to distributed in proportion to their ownership percentages. If after the $200,000 of combined guaranteed payments are made, SH distributes $80,000 of profit in 2018, only the $80,000 of profit would be potentially eligible for the QBI deduction. As a result, assuming there are no other limiting factors, Sean would receive a QBI deduction of $11,200 on his $56,000 ($80,000 x 70% = $56,000) share of the company’s profits, while Harry would receive just a $4,800 QBI deduction on his $24,000 ($80,000 x 30% = $24,000) of profits.

In a situation like this, making a one-time amendment to the SH Services’ partnership agreement could provide a significant tax savings to both partners. Consider that, in the aggregate, SH Services generated $280,000 of profit before distributions to owners (including guaranteed payments). To that end, Sean received a total of 55.7% of those proceeds, while Harry received 44.3% of the same total amount. Suppose then, that on the advice of their tax advisor, Sean and Harry update their partnership agreement to eliminate guaranteed payments and to reflect a change of ownership, such that Sean now owns 55.7% of SH Services, with Harry owning the remaining 44.3% (such a change in ownership could be structured as a sale of partnership interest from Sean to Harry or, perhaps, the transfer could be structured as a gift). If such a one-time change was made effective as of the start of 2018, both Sean and Harry would be entitled to exactly the same dollar amounts as they had under the old guaranteed-payments arrangement. The difference though, is that this time, every dollar of Sean and Harry’s partnership earnings can qualify for the QBI deduction. Thus, assuming no other limiting factors, Sean would entitled to a $31,200 QBI deduction on his $156,000 of partnership earnings, while Sean would be entitled to a $24,800 deduction on his $124,000 of partnership earnings (compared to just $11,200 and $4,800, respectively, under their prior arrangement!).

Notwithstanding the benefits of the above strategy, though, some caution is merited. Changing a partnership’s structure as in the example above can have a dramatic impact on partners’ outcomes if there is a subsequent material change in the partnership’s profits. For instance, suppose that in 2019, SH Services has a slower year and only generates $200,000 of profit. Instead of receiving the $100,000 of guaranteed payments he would have been entitled to under the old arrangement, Harry would only receive $88,600 (44.3% x $200,000 = $86,000). Conversely, if 2019 saw SH Services double its profit to a total of $560,000, Sean would receive just $311,920 ($560,000 X 55.7% = $311,920) of partnership income, as compared to the $352,000 (($560,000 – 200,000) x 70% + $100,000) he would have received had the old agreement remained in place. These potential consequences of the decision to restructure a partnership arrangement clearly illustrate that it’s a decision that should not be taken lightly, and in general will work better for businesses that otherwise have a stable income. That said, with a substantial tax break up for grabs, at the very least, it’s worth a discussion.

On the other hand, it’s also notable that in some cases, partnerships and LLCs may choose to zero out their “business” income in the form of guaranteed payments to the business owners, even though the guaranteed payments actually fully replicate what they would have received anyway, just to “ensure” that they receive the appropriate dollar amounts. In light of the QBI deduction, though, such a strategy would convert otherwise-QBI-eligible income into ineligible guaranteed payments. Thus, at a bare minimum, any partnership or LLC taxed as such that is making guaranteed payments should be reviewed to ensure that the guaranteed payments are still necessary (at all) given the current economics of the business!

Transferring (Some) Business Ownership to Non-Grantor Trusts?

IRC Section 199A reads, in part, “In the case of a taxpayer other than a corporation, there shall be allowed as a deduction for any taxable year…” (emphasis added)

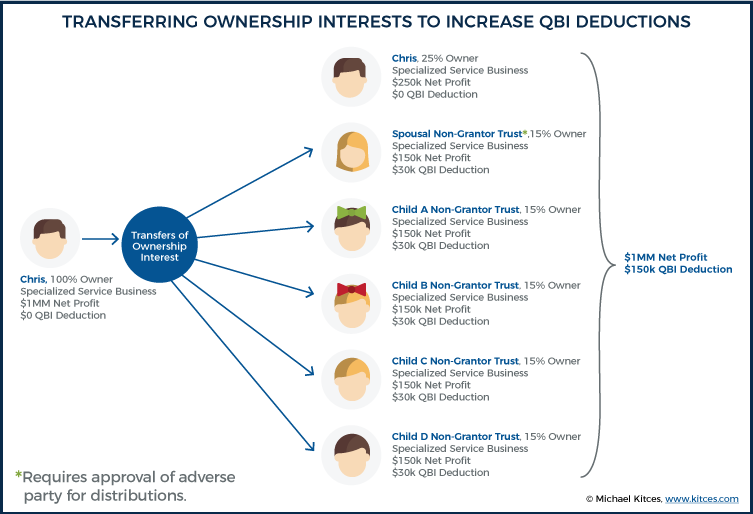

The significance of this language is that it does not preclude trusts from taking the QBI deduction. Which in turn creates a potential “loophole” in the law: ownership interests can be transferred to non-grantor trusts that will qualify for the QBI deduction when, if those interests had been retained by the current owners or transferred directly to the trust beneficiaries, such a deduction would not have been available.

Example 9: Chris is the owner of a successful business which falls under the specified service business umbrella and, after other 199A strategies have been implemented, his practice is still expected to generate $1MM annually in profits. Given Chris’s income, he will be unable to enjoy any QBI deduction on those amounts. Chris’s income more than covers his expenses. Additionally, he has two children, each high-earners in their own right, to whom he ultimately intends to leave his business.

One strategy to consider in a situation like this would be for Chris to create separate non-grantor trusts for each of his children, and to transfer a portion of his business interest to each trust, such that each trust would have enough shares to be able to generate up to $157,500 of business profits per year. Each trust would then be entitled to a $31,500 QBI deduction (ignoring other factors), as the trust’s income would be up to (but not in excess) of the phaseout threshold. Any remaining trust income could be distributed to the trust’s beneficiary annually and taxed at the trust beneficiary’s individual tax rates instead of the more draconian trust tax rates under the Distributable Net Income (DNI) rules. Thus, even though Chris’s children would not have been eligible for the QBI deduction had the business interest been passed directly to them, nor if it remained in Chris’ own hands, by virtue of using the non-grantor trust as a separate entity – which gets its own $157,500 of taxable income threshold before the QBI deduction begins to be phased out – the children are able to indirectly get the deduction anyway.

Notably, an additional trust could be set up for Chris’s spouse as well, but there would be an added complication in the case of a spouse. Due to the grantor trust rules (or more specifically, to avoid having the trust be deemed a grantor trust), distributions would not be able to be made without the approval of an adverse party. Absent this approval restriction, the trust would be deemed a grantor trust, and the income would be taxable on Chris’s own tax return, reverting it back to a disallowed QBI deduction instead of a non-grantor-trust-allowable QBI deduction.

For business owners generating substantial income annually, splitting business owner into one or multiple non-grantor trusts can be a home run. A separate non-grantor trust can be created for each of the business owner’s children and grandchildren, allowing the family as a whole to save substantial amounts in income tax annually (though to accomplish this the business owner is giving away substantial amounts of income today). Similar benefits may also be achievable through the use of incomplete gift non-grantor Trusts and non-grantor domestic asset protection trusts (DAPTs).

A few quick words of caution here though. You might be tempted to create multiple trusts for a child, grandchild or other person, each of which could get a QBI deduction provided the total taxable income for the trust remained below $157,500 (i.e. The Non-Grantor Trust I for Little Jimmy, The Non-Grantor Trust II for Little Jimmy, and so on). Oh, if only it were that easy! Unfortunately, it’s not. Section 643(f) treats multiple trusts established by substantially the same grantor(s) for substantially the same trust beneficiary (or beneficiaries) as a single trust if the principal purpose of the trust is tax avoidance… which let’s face it, this is! And no, you can’t transfer ownership between spouses and then have each of them create their own non-grantor trust for the same beneficiary either, because Section 643(f) also treats spouses as a single person.

And of course, it’s also important to bear in mind that a transfer of the business interest to a non-grantor trust is an irrevocable gift. So be certain the business owner is actually ready to give away shares of the business in the first place!

Other QBI Deduction Planning Ideas

Not every business owner will want or need to make some sort of massive change in entity structure or the creation of multiple trusts. For some, smaller, simpler changes could still produce meaningful tax savings. Consider the following additional strategies:

Minimize Portfolio Income To Avoid QBI Phaseouts

As noted earlier, the last thing a business owner wants to do is have Qualified Business Income and find themselves within or just above the phase-out range for the QBI deduction (especially as a specified service business where the QBI deduction phases straight down to zero!). And remember that while only the business owner’s Qualified Business Income is potentially eligible for the deduction, any income that increases taxable income could result in the reduction or elimination of an otherwise available QBI benefit. This includes income otherwise taxed at preferential rates, such as qualified dividends and long-term capital gains from a portfolio.

As such, advisors should be extremely mindful about managing taxable portfolio income for business owners within striking distance of the QBI deduction phaseout range (who might have that deduction reduced or eliminated with higher taxable income). The good news for advisors is that this doesn’t require the invention of any new strategies, but rather, merely places greater importance on tools that should already be a part of the tax planning arsenal. This might include placing greater emphasis on tax-loss harvesting and minimizing capital gains, moving away from dividend producing stocks in taxable accounts in favor of growth investments (and potentially creating synthetic dividends via stock sales as necessary), and the greater use of municipal bonds, as well as being mindful of proper asset location strategies to ensure the “right” investments (that generate the most taxable portfolio income) end up in the tax-sheltered retirement accounts. For some clients, stripped-down “Investment Only” annuities used only for their tax-deferral could also make sense if tax-deferred retirement plans and other strategies have already been exhausted.

[Tweet "Due to Section 199A, investment only annuities may become even more attractive to some clients!"]

Spread the Love to Those You Love With Family Income Shifting

Is the business owner within the QBI deduction phaseout range or just over? Do they have children that could potentially perform some type of bona fide service to the business (this could be as simple as cleaning the office, shredding papers, organizing files, etc.)?

Consider having the business owner employ their child (or other close loved one with little to no income). Doing so can help the business owner to lower their taxable income, and claim a (bigger) QBI deduction. What makes this tax play even better in 2018 (on top of the potential QBI benefits) is that thanks to the higher $12,000 standard deduction, children can now make up to that amount 100% income tax-free! (Note: $12,000 to be tax-free the income must be earned income. Otherwise, the kiddie tax would apply, which is even less favorable under the new TCJA rules.)

Business owners considering this approach should be cautioned that any persons receiving salary have to be performing (bona fide) services for the business, and the compensation paid for those services must be reasonable.

Get a Bonus for Not Taking Bonus Depreciation

As part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the Section 179 bonus depreciation deduction was significantly enhanced through 2022, after which point it begins to phase out. Under the law, a business owner can currently expense the total cost of qualifying property (generally depreciable property with a recovery period of 20 year or less) in the year of purchase. Taking advantage of the Section 179 bonus depreciation, however, is an option, and not a requirement. In certain situations, especially where without “regular” depreciation a business owner would be in or slightly over the QBI phase-out threshold, it may be better to avoid using the bonus depreciation and, instead, allow regular depreciation to help lower taxable income for many years.

In other words, if spreading out the depreciation deduction can get the business owner’s income below the line for multiple years in a row, consider leaving the deduction spread out, and don’t “bunch it” together into a single year as a Section 179 expense!

Play “Dumb” With Ambiguous “Specified” Service Businesses

There’s a lot of grey areas when it comes to the QBI deduction, but perhaps none of them are going to create more problems than the language used, in part, to describe a specified service business.

While some professions are explicitly included in the definition, the law also includes a “catch-all” provision for any business “whose principal asset is the skill or reputation of one or more employees.”

The concern this raises is that any advertisements or claims by a business owner that they are “the best” (or some similar statement) at anything could boomerang back on them by having them treated as a specified service business! More generally, it raises concerns for any service business that has a “celebrity” or high-profile employee.

It’s probably a marketer’s worst nightmare, but to help an on-the-fence type of business continue to avoid classification as a specified service business, a company might want to go out of its way to avoid using such language in promotional and other materials… at least until the IRS and Treasury issue widely anticipated further guidance on the issue later this year.

Make Use of Other Deductions

Is there a business owner stuck in the phase-out range for the QBI deduction? Then consider other ways they might be able to lower their taxable income. Maybe they should consider giving away more money to charity this year? If their within the phase-out range, that decision essentially boils down to the following; would they rather give charity one dollar, or the IRS about 47 ½ cents? You might even think of it like this… for the business owner in the phase-out range of the QBI deduction, for every ~53 cents they give to charity, the IRS will match their donation with ~47 cents. Tough to say no to that, right?

Additionally, if a business owner’s taxable income is unusually high for a particular year, the use of a donor-advised fund could be particularly attractive. While the cash-flow to make a larger-than-normal contribution to the donor-advised fund could be an issue, the business owner will likely never see a greater tax benefit for making the contribution... which is precisely when the use of a donor-advised fund makes the most sense!

Ultimately, even the broad range of strategies discussed above are only the beginning for the QBI deduction. New, innovative ideas are almost certain to continue being thought up as time passes, and once we get further guidance from the IRS. That said, there’s already more than enough reasons to reach out to business-owning clients today to begin to discuss how they can make the most of this new tax-saving deduction!

So what do you think? Are you talking about proactive Section 199A strategies with your small business owners? What strategies do you think will be most advantageous to small business owners? What other strategies might arise related to QBI deductions? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Leave a Reply