Executive Summary

While much has been written about the inherent benefits of delaying Social Security benefits to age 70, a fundamental challenge in the real world is that the decision cannot be viewed in the abstract. The decision to delay Social Security isn't just about the value of delaying, but also about the money that must be spent from the portfolio to sustain spending in the meantime, and/or the decision to allocate money towards delaying Social Security and not towards other fixed income investments or a commercially available lifetime immediate annuity.

Yet a deeper look reveals that when viewed from an investment perspective, the decision to delay Social Security actually represents an astonishingly valuable "investment" return, based on the internal rate of return of the cash flows that it provides over time. While it is certainly unlike other more "traditional" investments, in that its return is based not on interest rates or market performance but on the longevity of one's life, for those who do live a long time the decision to delay Social Security can produce real (inflation-adjusted) returns of 4%, 5%, or even 6% for those who live into their 90s and beyond.

Calculated in this manner, the reality is that for those whose greatest retirement "risk" is living far past life expectancy, the decision to delay Social Security can actually be a highly beneficial investment, with a real return that dominates TIPS, is radically superior to commercially available annuities, and even generates a real return comparable to equities but without any market risk! Of course, there is still an aspect of "mortality risk" inherent in the decision to delay, but for those who are most concerned about living a long time and funding a long retirement, the decision to delay Social Security - even if it means partially spending down the portfolio in the meantime - can actually be the best means to securing a successful retirement, by converting the uncertainty of market returns into the certainty of higher Social Security payments!

Adjusting Benefits Based On Social Security Timing Before/After Full Retirement Age

The rules for Social Security allow for a certain benefit at full retirement age, which is then adjusted upwards or downwards by beginning early (as early as age 62) or delaying until later (as late as age 70). For every year benefits begin early, they are reduced by 6.66% per year (up to 3 years, and then reduced by "only" 5% for additional early years), and are increased by 8% per year (until the maximum age 70) for starting late. Because the exact "full retirement age" itself varies between age 65 and 67 depending on year of birth, the exact magnitude of the adjustment will vary. For those born between 1943 and 1954, who will be age 60-71 this year, the full retirement age is 66, which means starting at age 62 will reduce benefits by the maximum 25% (3 years x 6.66% = 20% plus 5% for the 4th year = 25% reduction), and delaying them to 70 will increase by the maximum 32% (4 years x 8% = 32% increase).

In dollar terms, this means an individual who was otherwise eligible for a $1,000/month retirement benefit at full retirement age would have benefits reduced by 6.66% to $933/month by starting a year early, or increased by 8% to $1,080/month by delaying a year. At the extreme, that individual would only get a $750/month benefit by starting as early as possible (at age 62), or could get as much as $1,320/month by waiting as long as possible (to age 70). (Notably, these benefits would also be adjusted annually for cost-of-living adjustments, so these represent real inflation-adjusted benefit amounts at various ages). On a relative basis, this means the decision to delay benefits by the full 8 years from the earliest possible (age 62) to the latest possible (age 70) actually increases the inflation-adjusted benefit by $1,320 / $750 = 76%.

Often the decision to delay benefits is explained as being the equivalent of an 8% annual return (for those delaying past full retirement age), or a 76% cumulative return over 8 years (for delaying all the way from age 62 to 70). However, the caveat to making the decision to delay is that it also has a non-trivial "cost" in the form of benefits that aren't received (and can't be invested or consumed) today. While this certainly doesn't eliminate the value of delaying Social Security benefits, it does make the trade-off more complex and nuanced than just (incorrectly) equating it to an 8%/year (or 76%-per-8-years) returns.

Calculating The Benefit Of Delaying Social Security

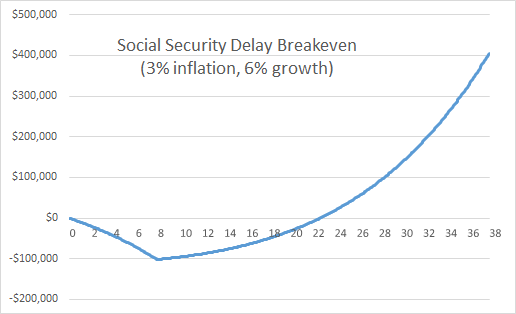

To value the trade-off of delaying Social Security - no benefits paid now, in exchange for incrementally higher benefits in the future - we must calculate the economic value of the exchange. Accordingly, the chart below shows the impact over time of not receiving $750/month (increasing annually for inflation) from age 62 to 70, which then begins to be offset by the higher (inflation-adjusted) payment stream that begins at age 70 itself. Since benefits not paid from age 62 to 70 represents a foregone investment opportunity (either the money could have been invested if it wasn't needed, or it could have been consumed and thereby allowed other assets to remain invested), we must account for not only the $750/month (at age 62) versus $1,320/month (at age 70) benefits, but also for inflation itself (assumed here to be 3%) and this time-value-of-money factor (projected at 6%, a "balanced" portfolio rate of return that could have been earned on the money invested or not-consumed).

As the results reveal, it can take a long time to “recover” from not receiving $750/month (and having the opportunity to invest it, or keep an equivalent amount invested by having the Social Security dollars available to spend). The “breakeven” period with these assumptions is just over 22 years; or stated another way, for the individual who chooses to delay from age 62 until age 70, it takes until beyond age 84 just to recover the economic value of having waited. Notably, though, beyond that point the benefit in favor of delaying Social Security continues to accrue, exponentially, as the compounding time value of money now works in favor of the delay decision, in addition to the fact that the higher delayed benefit is also enjoying ongoing cost-of-living adjustments.

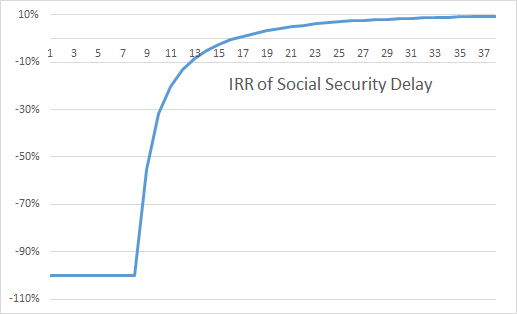

Of course, the point to breakeven is sensitive to the return assumption used. At a greater rate of return, the breakeven takes longer; with more conservative return assumptions, the breakeven is reached more quickly (as there’s less impact to delaying Social Security if the foregone dollars are assumed to not have been able to earn much anyway). In fact, another way to look at the situation is to determine what breakeven rate of return would have been necessary at various points along the time horizon to have achieved a comparable result; in essence, this is simply an analysis of the internal rate of return on the decision to delay (and foregone payments) compared to the higher dollars ultimately received.

As these “Internal Rate of Return” (IRR) results show, delaying Social Security is a “risky” proposition, in that passing away shortly after the delay results in a total loss of foregone payments. Once benefits begin after year 8, it still takes another 8 years for the “excess” payments to make up for the years that early benefits weren’t received (i.e., the IRR crosses 0%), and then another 6 years until the IRR actually equals a 6% growth rate (8 years + 8 years + 6 years = the 22 year breakeven shown earlier at a 6% growth rate).

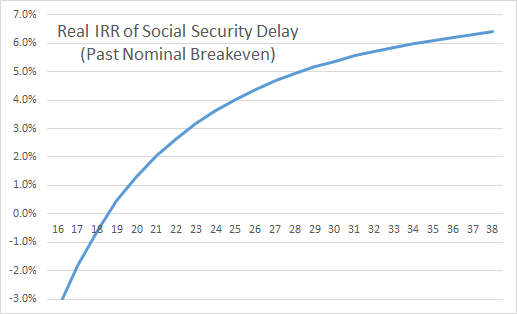

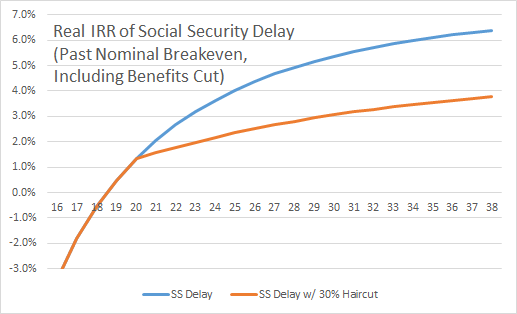

However, beyond that point the IRR continues to increase… on what, in the end, is a “guaranteed” rate of return backed by the Federal government. In fact, the implicit “return” of delaying Social Security is not just a nominal return, it is also a real return, since benefits are adjusted annually for inflation (which was assumed above to be 3%). Accordingly, the chart below shows how the real (inflation-adjusted) IRR trends in the later years, starting in year 17 (when it turns positive) until year 38 (when the individual would be reaching age 100).

While by definition these real returns are only available to those who live to later years at or beyond life expectancy, the results are quite significant. Those who reach age 90 (which would be the 28th year after delaying) have generated the equivalent of a 5% real rate of return in what is essentially a government-backed bond!

Comparing Social Security Delay To Alternatives

Delaying Social Security Versus Bonds

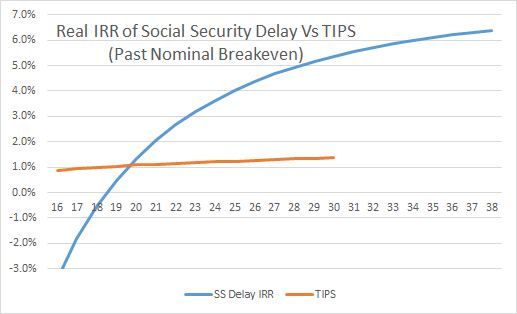

Given the charts above showing the implicit return generated by delaying Social Security, we can compare the value to other investment alternatives. For instance, the chart below shows the real IRR on delaying Social Security versus a comparable TIPS yield along the current yield curve.

As the results show, it does take until nearly year 20 before the real return of delaying Social Security is superior to the results from a TIPS yield. However, beyond that point, the economic value of delaying Social Security continues to rise dramatically, producing a real return that is multiples of a comparable risk government bond! And notably, the available return from TIPS ends beyond the 30-year market (there are no longer-dated government TIPS available today), while the value of delaying Social Security just continues to compound higher for those fortunate enough to live long enough!

Delaying Social Security Versus Immediate Annuities

Another way to compare the value of Social Security – which is ultimately a lifetime stream of payments – is to compare it to other commercially available annuities.

Accordingly, we can compare the higher payments received by delaying Social Security benefits from age 62 to 70, to the payments that would be received by accumulating those early payments and simply buying a commercially available immediate annuity at age 70. For these purposes, we assume that the inflation-adjusting Social Security payments from age 62 to 70 are accumulated in a conservative government bond fund (since the time horizon is fairly short) with a 2% growth rate. With a $750/month payment (which was $1,000 at full retirement age, reduced by 25% for starting early) the cumulative value of the benefits would be $86,587 by the start of age 70.

To compare, the chart below shows what can be purchased from a commercially available annuity for males and females at age 70 with $86,587, either on a nominal or CPI-adjusted basis. By comparison, the decision to delay Social Security over those years produces an excess payment of $722/month at age 70 (which is $1,320 with delayed retirement credits, plus 8 years of 3%-assumed cost-of-living adjustments to produce a $1,672/month nominal payment, reduced by the $950/month inflation-adjusted payment that would have been available by having started benefits immediately at age 62).

| Monthly Annuitization Income of $86,587 For 70-Year-Old | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Annuitization | CPI-Adjusted Annuitization | Social Security | |

| Male | $572.20 | $425.61 | $722.00 |

| Female | $537.11 | $399.76 | $722.00 |

(Thanks to John Olsen and Cannex for providing immediate annuitization quotes for this research!)

As the results reveal, the payments produced by Social Security dominate the nominal or real payments available from a comparable commercially available annuity. This appears to be due primarily to the assumptions that are embedded in the Social Security formulas and benefits, many of which were built when longevity was shorter and interest rates were higher; compared to annuities available today (which use current longevity and rate assumptions), the Social Security delay decision is far superior. Which means, in essence, if a retiree has any plans annuitize assets at all, the “best” annuity to be had is actually to delay Social Security benefits (where the “purchase price” are personal assets spend from age 62 to 70 while waiting for the higher Social Security payments to begin).

One important distinction, though, is that Social Security – as it is essentially a “straight life” annuity – does represent a “riskier” form of annuity, in that any death that occurs during the 8-year delay time window results in a total loss, and also that there is not a “period certain” option to ensure payments will continue for a specified number of years as is the case with commercially available annuities. On the other hand, the annuity quotes above also assume no period certain payment, and the inclusion of such a payment would just make the commercial annuity quotes even lower and the Social Security delay look even more appealing. Ultimately, there is a legitimate risk trade-off here for retirees to consider, though arguably the “cost” of getting a floor for those payments is quite significant. In addition, it’s notable that for couples where the higher payment for the individual is also a higher survivor payment for the couple, these delayed Social Security benefits are essentially joint survivorship payments, which makes them even more appealing (as the commercial annuity rates above would be significantly lower if priced for joint survivorship rather than a single life male or female!).

Delaying Social Security Versus Growing Investment Assets

For many, the decision about whether to delay Social Security benefits is not merely a choice about when benefits begin, but a choice about whether portfolio assets will be spent while waiting for the higher payments to start. Which means, ultimately, that the decision to delay Social Security benefits must be discounted by the opportunity cost of not being invested in the portfolio. Or viewed another way, delaying Social Security will only be appealing if the IRR of the Social Security delay produces a superior risk-adjusted return to the return that could have been obtained via the portfolio itself.

In this context, we can refer back again to the implicit real return over time generated by the decision to delay Social Security benefits. As the chart revealed, while it takes many years for the real rate of return to merely turn positive after delaying benefits, in the later years the real returns become very large, crossing about 1.3% after 20 years, 4% after 25 years, 5% after 30 years, and 6% after 34 years.

By contrast, the long-term real return on equities has been “only” about 7%, which represents a 7% equity risk premium over an alternative risk-free rate. Which means for equities to generate a comparable risk premium over the value of delaying Social Security, equity real returns would need to be 8.3% after 20 years, 11% after 25 years, 12% after 30 years, and 13% after 34 years. Arguably, these are questionable real returns to expect in any environment, and even more questionable in the context of today’s above-average valuations.

It’s also notable that these results hold true even if we do nothing to fix the current Social Security shortfall, where the trust fund is projected to run out in roughly 20 years and benefits could only be paid from current Social Security taxes – which would not actually "end" Social Security payments at all, but merely would result in a 30% haircut in benefits starting in 20 years. Yet as the chart below shows, even if the shortfall occurs – i.e., we do nothing to fix the system with adjusted benefits, or higher taxes, at any point in the next several decades – the internal real rate of return over the long run is still compelling. And to the extent we make adjustments sooner rather than later, either through more modest changes to benefits, or an increase in Social Security taxes, the orange line will simply move even closer to the original blue line.

Which means that ultimately, delaying Social Security benefits provides superior risk-adjusted returns to equities and portfolio investing in the long run, both with the current system and even if it’s not otherwise “fixed” as well. Obviously, this is not true in the short run – as noted earlier, it takes more than 15 years to breakeven at all. Yet if the retiree’s time horizon was that short, the proper investment would not likely be equities anyway. In scenarios where there is a long time horizon, and the retiree wishes to hedge longevity by owning a portfolio with long-term growth assets, the reality is that delaying Social Security becomes the superior “long-term growth asset” for the retiree. In other words, spending portfolio assets to delay Social Security becomes the equivalent of liquidating a “low” return asset to buy a “higher” return one instead!

Delaying Social Security As The Best Long-Term Return Money Can Buy

Social Security, and the decision to delay benefits represents a unique form of “investment” – a return that is contingent not upon interest rates or market performance, but survival and longevity. Of course, it’s worth noting that because the value of the Social Security delay decision is contingent on how long someone lives, it is clearly not beneficial for those who are in poor health or are otherwise not optimistic about living a long time (though be certain to look at joint health and longevity in the case of couples planning for survivor benefits, not to mention other couples-specific strategies like File-and-Suspend that may further impact timing decisions).

Nonetheless, the decision to delay Social Security can be evaluated based on the implicit rate of return it creates by choosing to delay, and over longer time horizons – when clients may “need the money most” as they have more years of retirement expenses to cover in the first place – the return of the Social Security delay becomes quite compelling. In fact, the return is generally far superior to any risk-adjusted returns that can be achieved over comparable time periods by the available alternatives, whether investing in risk-free bonds, growth equities, or buying a commercially available annuity. And because the system is indexed to inflation, its real returns will be maintained even if inflation rises, and will only become better if longevity continues to increase as well. In fact, ultimately the decision to delay Social Security delivers the best results when there is either unexpected inflation, unusually long longevity, or especially bad market returns, which are the exact three scenarios that traditional portfolios are the least effective at managing, making the decision to delay Social Security the ultimate form of “anti-fragile” triple hedge!

Outstanding review Michael! Nice to see someone cover this topic and address the impact of not receiving Social Security during the age 62-70 time period. In addition, this is the only article I have read that discusses and quantifies the risk of a future Social Security shortfall.

One area not mentioned, perhaps justifiably, since it affects a subset of the married population, is the GPO (Government Pension Offset). Depending on each personal scenario, many federal, state and local employees’ spouses will have their survivor benefits reduced, or eliminated, if they receive a federal pension. This may change there view of the risks associated with delayed benefits.

FWIW, in my opinion, the decision to delay has four drivers, which should be addressed in the following order:

1. Do I have the financial wherewithal to delay benefits? If not, no need to continue.

2. A health risk assessment to address passing inside of the breakeven point.

3. A survivor benefits analysis that may offset some of the health related risk.

4. An investment analysis.

In this context, a discussion with your healthcare provider is just as important as the advice from your financial planner.

Thanks again for a great article.

Fantastic article, Michael. This deep analysis of delaying benefits within the context of alternative investments is exactly what the financial advisory community needs to truly help people with their claiming decisions. What’s so interesting is how much more valuable the delay becomes later in life. Whether you see it as an investment or insurance (two concepts that are sometimes at odds with each other — one builds on hope, the other on fear), the common thread is the long life. How long each of us ends up living is the great unknowable. Doesn’t it make sense to ensure the best outcome just in case we do make it to extreme old age? I do wonder, though, how long it will take Congress (or SSA) to revise the formula for delayed retirement credits to bring them in line with today’s mortality and interest rate assumptions.

So, no Social Security payment increase? Then there should be no increase in the federal governments salaries! Most seniors will see increases in some of their medications as high as 400 to 500% or more! Groceries, especially beef and eggs, not to mention most produce is skyrocketing out of sight!

In fact, most people are under-employed and can’t afford to live. We must now purchase health insurance we cannot afford and do not want or need (mine is $450/month… contrast this to my $25/month auto insurance from InsurancePanda… or my $12/month renters insurance… both private-enterprise!)

The only thing that is SLIGHTLY less costly right now is gasoline and that can go up anytime the greedy oil tycoons decide they need to increase their salaries and perks! It is time to give seniors the increase they deserve before the goons in congress find some other reason to rob our funds that we contributed to all our working lives!

Michael, may I add one important point? For those at just the right level of withdrawals from pretax retirement accounts, Social Security benefits will be taxed fully. By using your method of delaying the benefit, the retirement accounts can be drawn down, via withdrawal or Roth conversion, so when the SS benefits are taken, they don’t trip any tax on the benefit itself. This magnifies the positive impact of delaying one’s benefit start date.

Given that the thresholds for “provisional income” used to determine Social Security taxation are not indexed for inflation, it is tough to avoid taxation on SS benefits. To the extent delaying benefits means you will be paying tax for fewer years, though, I agree there could be an income tax benefit. Remember also that only half of the SS benefit is included in the provisional income formula so SSI is inherently a more tax efficient stream of income; if SSI comprises a greater portion of your income in retirement, you will pay less in income taxes as a result.

“file a federal tax return as an “individual” and your

combined income*is more than $34,000, up to 85 percent of your benefits may be

taxable.

file a joint return, and you and your spouse have a combined

income*that is more than $44,000, up to 85 percent of your benefits may be taxable.”

I wrote an article titled “The Phantom Tax Rate Zone” that shows the impact of this taxation. The next $1000 IRA withdrawal creating an incremental $462.50 in tax due. This for a single who would otherwise be taxed at 15%. Keep in mind, there are those with such a high income at retirement, there’s no avoiding this, and those so low, they wont be impacted. It’s those who are in a certain range that can benefit from good planning.

Would love to read your article and get your thoughts…. I am currently weighing pros and cons of suspending age 66-70;

CONS: Loss of investment opportunity, i.e. “the time value” of money, contributing to long breakeven period; intangibles related to control, etc…

PROS: Opportunity to do Roth conversion w/out the incremental tax trigger that you mention…

http://rothmania.net/the-phantom-tax-rate-zone/ is the article link. It was posted in 2012 with 2011 rates, but the nature of the phantom rates is no different today, just shifted a bit to adjust for inflation. I like the idea of using a period of time to convert while delating SS benefits. The benefit grows 8% each year, and the Roth is not triggering the SS tax, as you aren’t taking any benefit early on.

You are making the assumption that social security is almost like a government sponsered annuity. As we saw in November 2015, Congress significantly changed social security rules with very little grace period for those almost at retirement age. What happens when the next Congress decides to do social security adjustments for total assets and/or other income? Or in other words turn social security into a modified welfare benefit? How do you plan for you social security future if Congress can change the rules at any time?

Unfortunately, you are correct. The biggest risk, as you state, is that our congress will use Roth withdrawal as a gate for SS taxation. I’d be horrified, but not surprised at that. The idea that 13% (including employer deposits) of my money was taken for 3 decades and yet, I’m not quite entitled to any bit of it, is disconcerting to me.

To answer directly, your last question, I couldn’t retire until I had enough of my own money. SS will be a bonus if it’s there when I’m eligible.

Left out of this discussion is the taxation of Social Security benefits for an individual, married or single who is continuing to work past 66 and who has a high annual income. The Social Security benefit could be taxed at 25%- 40% which would affect the time value of money that is built into most analyses. by wiating till age 70, salaried income would be removed and the social security that is netted would be higher thereby lowering the “break even” age

For those with earned income after becoming SS eligible (whether from actual work, Employee Stock Options, or whatever), they should also consider the Earned Income Adjustment that SS will make to your “early SS benefits” if you elect to start SS benefits at age 62 (for example), but continue to receive earned income thereafter. The Earned Income Adjustment could significantly reduce the early benefit that SS will actually pay, and hence cause one to question whether taking early SS while still receiving earned income is really a good idea (even if you otherwise would have, were it not for the Earned Income Adjustment)

Surprised favorable taxation of Social Security doesn’t come up more often in these discussions. Because SS can double at twice the rate of ‘other’ income for same level of taxation. So maximizing SS reduces likelihood or intensity of SS tax torpedo, by increasing ratio of SS to non-SS income.

For this and the reasons Kitces cited, planning on delaying SS to 70 if at all possible, despite my family’s relatively poor longevity. Sort of like an ersatz QLAC.

If we had delayed Social Security until age 70 then our income would be such that our Medicare premiums would be much higher…Part B, Part D and supplement.

Misawa,

Yes, it is true that higher income in general can result in higher Medicare Part B and Part premiums. I’ve written about this separately – see http://qa.kitces.com/blog/income-thresholds-for-medicare-part-b-and-part-d-premiums-an-indirect-marginal-tax/

However, pushing you over one “threshold” line for Medicare premiums still amounts to “only” a few hundred dollars a year, while the increased Social Security benefits for delaying are many multiples of that. It would certainly somewhat diminish the value of the delay, but shouldn’t make it negative.

That aside, if your income is high enough as a couple for this to be an issue – starting at $170,000 of AGI – it also raises of the question of whether other income could be managed effectively to navigate the Medicare premium threshold. Given that most your Social Security benefits would only likely be 1/4th to 1/3rd of your income, there is far more to manage here than “just” the impact of the Social Security benefits delay.

– Michael

It seems to me that if one has substantial assets, then it might not benefit to delay SS payments. With a 22 year break even scenario, why take the risk that one might not live that long? If income is a concern along with longevity, then it might be worth that risk. Conversely,for the person with substantial qualified assets, might it not be better to delay SS and spend down the qualified assets? Then when RMD’s are required, there will be less taxable income. Or will it be a wash?

I’m skeptical that accelerating withdrawals from tax advantaged retirement accounts to avoid paying “more tax” on RMDs really makes sense. Even if you expect to be in a higher tax bracket after RMDs begin, you still need to consider that you are destroying (and perhaps throwing away) tax advantaged growth potential (by accelerating IRA withdrawals). If one considers this, and the discounting of future taxes on RMDs, you may well find that you are destroying value by accelerating IRA withdrawals (unless you expect to deplete your IRA assets very quick after age 70 1/2 anyway, in which case RMDs are not really the issue).

No, because you would actually spend taxable assets first and do Roth conversions for the “accelerated withdrawals.” This trades tax-deferred growth for tax-free growth.

I was just commenting on the wisdom of accelerating withdrawals from a traditional IRA into a lower tax rate environment. If the only withdrawals you ever plan to make from the traditional IRA are the RMDs, I remain skeptical (because that does destroy long term tax deferred growth potential, which might be more valuable than the lower tax rate). But if you are going to withdraw from the IRA “fairly quickly” anyway, it could make sense. One really needs to do the economic analysis for their particular situation (there is no one right answer).

What you are proposing sounds like a conventional Roth Conversion (which is a different idea) — and Roth conversions can make sense, but again depends on how much conversion tax you pay (and the opportunity cost thereof), as well how long you will leave the “reinvested” funds in the Roth vs Traditional IRA account. Again, no one right answer. One just needs to do the economic analysis (for their particular situation).

I wasn’t contradicting you really, I was explaining the scenario in which you wouldn’t lose benefits of tax deferral. I was pointing out the strategy I would use for someone who retired in a given year (age 65, for example) and delayed taking social security until 70. From age 65 through 69, I would have them withdraw money from their taxable account to fund their living expenses. During these few years when they have no other income (SS has not started yet), you can do fairly large Roth conversions each year without paying much tax. At age 70, you’re left with a significantly lower balance in your IRA and a hefty Roth account. Then you leave the Roth to grow and draw from the IRA.

I understand completely, as that is exactly my situation, and my plan! One other thing that some may want to consider — you can also use that “low income valley” between retirement and RMDs to realize capital gains at 0% (under current tax law), and it looks like this will survive in the pending tax law changes. Some may wish to consider whether this or partial Roth Conversions (or some of both) are the best use of that limited “space” (under the new/pending tax rules, which could effect the economics of Roth Conversions, or the maximum tax rate at which they are economic). Also, I misspoke in my comment above, when I said that you needed earned income to “at to the Roth”. If you do it via a Roth Conversion (with IRA distributions other than RMDs) you obviously don’t. Good luck!

Let me add my voice to the chorus – great article, Michael! To those (other than those with clearly dim actuarial prospects) who would say, “What if I die?” inside the B/E point, my response is a resounding, “But what if you LIVE?!?” and this article hits that nail square on the head.

I would like to ask, for those who need a financial bridge to span the income requirement gap from 62 to 70, what would be the implications of using a reverse mortgage (assuming the requisite equity is available) to provide that bridge? No doubt the accrued interest expense must offset the ‘protected’ portfolio returns during that 8 year period, but the math is beyond me. Would you recommend or discourage use of a reverse mortgage for this purpose?

Well done Michael.

To take the subjectivity of “when I might die” off the table, though, I’d suggest the IRR evaluation (singular) include discounting for mortality (appropriate to the individual), to come up with one overall inherent rate of return.

On this basis, unfortunately, delaying isn’t as rosy purely as an investment. That said, delaying certainly is beneficial along many of the lines you discuss, most importantly a more satisfying retirement after one does reach70, no matter how long they live thereafter. Moreover, for many, taking SS early may be a disincentive to scratching a bit longer for earned income while they still can.

while I certainly no expert, these report seems to be one of the best summaries of the decision to delay or not I have read. Having said this, it appears to leave out one other key component, that is “will social security be around at fully payment levels over the long run?’

Most reports I read suggest at current estimation the fund will only enable full payments until sometime around the mid 2030s, and if accurate, this has to dramatically impact the economic decision of delaying. IMHO.

Scott,

The entire last section of the article discusses this exact issue, including showing the consequences if we do NOTHING to adjust and “fix” the system and allow for the total depletion of the trust fund and the associated benefit cuts that must occur along with it.

As the chart shows, this does impact the economic decision a bit (though not as much as many suggest).

– Michael

Fantastic discussion – coming from thrifty consumer in good health, who has achieved their retirement targets. My spouse and I have been tackling our concerns over funding a long life. With certainty, we can avoid touching principal from age 62-70 (short of a truly Great Depression in the intervening 10 years), so the question was how to tackle the “risk” of living a long time. Delaying SS for both spouses may be in order. I’d also like to mention the benefits this has on not elevating income during the ages 62-70 when there may be the opportunity for continued earned income. Another benefit is that, as we age, our vacations can become more expensive (think cruises, not mountain hikes) – a recurrent monthly income 76% greater than the alternative can certainly allow for a nicer transition to lifestyle choices that would have occurred in any event!

I think waiting is poor advice for those who need the money to live off of or need it to live a reasonable comfortable life in early retirement. But it is transparently obvious that this advice is not meant for those folks. For all others the suggestion is spot on. Setting yourself up for the maximum compounded return for the rest of your life makes enormous sense.

This is the fact of the matter. Those folks who have “a lot of money,” this analysis just states the obvious, i.e., I don’t need the extra money right now, so I guess that I will wait awhile to receive my SS benefits. Those without a lot of cash assets will require the extra money as soon as possible to pay the bills. This whole discussion seems to be a bit intuitive to me.

You make a valid point. However as I read the responses to this article and the many others that cover the same issue I see a pattern. A significant number with the means to wait focus on getting as much as they can back and for them it means starting early. Waiting is using time as a payment for the best annuity you can get. Many, perhaps most, of the “grab the money now crowd” will burn through their savings and live to a very old age with little monthly social security income coming in. I see this coming, financial advisers see this, and as does the government. For everyone having destitute elderly boomers 15 or 20 years from now does no one any good. Asking people to wait can help mitigate such a problem.

Agee that those who need to the money sooner to cover expenses don’t have much choice but to take. However, those who have “allot of money” should not be too worried about income security in later life, so they can so they can afford to either take SS benefit early or delay them, whichever they believe has the most long term economic value. I conclude that for “those who can choose” the better (risk adjusted) investment decision is actually to take SS early, and reinvest that money elsewhere — as SS never really rewards you very much for the longevity risk that you take by deferring (vs what you could achieve by taking early benefits and re-investing elsewhere). So, ironically, it seems that those who need the money should take SS early, and those that don’t should probably take it early also. SS is really an insurance program for those “in the middle” who are primarily concerned with income security in later life (i.e. outliving their retirement assets), and willing to forego some economic value in order to achieve it. And for those folks (primarily) deferring SS could make sense (even though it is not a great investment option).

Great analysis!

Thanks for this excellent analysis. My only concern about delaying Social Security is my concern that benefits may be reduced in the future as the system approaches insolvency. I’d rather take Social Security at my full retirement age and not spend assets to delay it further. At least I’ll have control, rather than trusting the government to maintain my SS benefit and the planned cost of living adjustments.

Joanne,

Per the chart in the article, EVEN IF Social Security is NEVER FIXED, in ANY WAY, it is STILL a relatively appealing value proposition to delay, because the reality is that ONLY the trust fund is being depleted, and at the extreme the trust fund ONLY funds 25%-30% of benefits for the next century anyway, and the benefit cuts wouldn’t even begin for 20 years. See http://qa.kitces.com/blog/latest-social-security-trustees-report-for-2013-confirms-most-benefits-will-still-be-paid/ – and again, that’s if we do NOTHING to fix the system. If/when/as we adjust benefits in the meantime, raise Social Security taxes, or otherwise adjust, the changes are even milder.

Simply put, the overwhelming majority of Social Security benefits have NOTHING to do with Social Security’s trust fund, or its “solvency”, and the common media pronouncements of Social Security’s prospective “insolvency” GROSSLY overstates the actual consequences based on how it’s funded. All Social Security requires are workers paying payroll taxes, which are used directly to fund Social Security benefits – which is actually how the system has already worked for the past nearly 80 years.

– Michael

Fabulous analysis, it reinforces the Barry Sacks Ph. D. and Stephen Sacks Ph.D. research. Great article

Micheal great article. Delaying SS has an outcome very similar to the effect of purchasing an inflation – adjusted DIA 10 years or more prior to the intended income start date. A commercial delayed income annuity allocated many years during the working years prior to retirement, mathematically provides a nearly identical IRR outcome for those who live long. Couple SS delay with proper product allocation utilizing DIAS for optimal retirement planning can have a remarkable “one – two punch” of providing tremendous value. Thanks for such a great article!

Curtis Cloke

Wouldn’t purchasing a QLAC at 56-62 which kicks in at 80 also provide the longevity protection-as 80 is the crossover point for most? Either forego the income from 62-70..which is a bet that you will live to 80 or buy a QLAC which is also a bet that you will live to 80. oh yes…I enjoyed your RICP lectures….

You’ve discord many factors and issue in your blanket statement, the first of which assumes no flexibility.

I have done a lot of searching for well researched articles on when to take benefits and this one is the best so far. The only thing I question, however, is the liklihood of living long enough to reap the benefit of delaying vs spending down ones savings. The real benefit kicks in after age 90 or so and most people won’t achieve that age. I use the “pancake” method of setting aside money for each decade I might live and accept the fact that I might wind up very elderly and somewhat broke. At that point however, the decision of whether to continue to attempt to live more years that no longer might be enjoyable would be an easy one for me.

Great post! Calculating the benefit of delaying social security can be confusing.

***

It dawns on me that there is a difference in how the two “annuities” (private vs Social Security delayed credits)

are priced based on the behaviour of the population that they reach.

Essentially everyone is in Social security. Those that are healthy and

those that are not. If you expect to live long, you might opt to wait

gaining additional monthly income. Basically you are buying additional

annuity income with your foregone SS benefit payments. Those that expect

to die early take their payments early. But, you can’t begin until age 62 and by age 70, everyone is in the pool –

and so the “delayed credits” annuity is priced reasonably fairly. In fact SS uses outdated mortality tables that probably under price the cost of the delayed credits.

If you buy a private insurance annuity – neglecting the profit motive –

Those that expect to live long should be, and probably are, more likely

to buy an annuity. Those that expect to have a short lifetime should,

and probably do, forego annuity purchases in favor of self funding and

leaving a legacy. To that end, the serviced population is not the same

as that serviced by SS. Not everyone is in the pool. The result is that

the annuity purchased privately must be more expensive than the one

purchased with SS delayed credits. They not only have to use up to date mortality tables, but must adjust those tables to reflect the serviced populations mortality – not just the population at large. And that is true even before you add

in the cost of providing a profit to the insurer.

Great article…I just found it. One more benefit to delaying SS until age 70 is taxes. The formula for taxing SS benefits is complicated, but if you have a 60-40 relationship of SS income to other income, as opposed to a 40-60 relationship, you will pay less taxes. The higher the ratio of SS to other benefits, the lower your income tax bill. Also, some states, like mine, do not tax SS benefits at all, so there’s an immediate tax savings on the state level. Of course, tax law could change, but I’m not betting on that happening.

True, but some (who may have substantial assets in traditional retirement accounts which are subject to RMDs) may actually be in a higher income tax bracket once RMDs begin (at at 70 1/2) then they might be from age 62 to age 70 1/2 (particularly if they are living off of Taxable Saving during this period, which doesn’t generate a large income tax burden). So for those folks the “increase in SS benefits” that they get by deferring could be at least partially eroded by higher taxes (when they eventually collect)? It all depends on ones specific situation, but you are right to point out that tax implications should be considered (although probably not the primary decision driver).

Michael:

This question comes from a 60 year old male born in July (the wife is also 60 and born in Nov). We were talking about your social security report from The Kitces Report Volume 1, 2016 (he references a number of pages in the inquiry ).

What do you think about his thought process (That you do not really get a COLA on DELAYED social security…the COLA comes when you turn on social security!) And therefore, you should NOT count it in the calculation…

“The point we discussed about what appears to be a missing factor in the 20 page analysis.

That is, COLA’s don’t start until someone starts collecting SS. Thus the “haircut” per year is 6% or so a year before FRA MINUS the COLA amount (and 8% MINUS 3% for bonus between FRA and 70). So, if the COLA is 3% (a reasonable long term average), and investment returns are 4% a year on IRA savings not withdrawn for expenses, then for the years between claiming early, and whenever a later start point is calculated, I don’t see that there is ANY haircut. Further, a compounded 3% COLA for 4.33 years means the initial base amount will have grown by 13% or so (even a 2% COLA would approach 10% by FRA).

In the graph shown on page 7, it would seem this would push the payback period further out than shown, such that even at a paltry 4% growth (minimum shown) the payback period has to exceed 20 years. If this is correct, we may want to claim mine early as well.”

Michael: I left this comment on your 4-8-15 article, then found this more relevant article. Here’s my post, with an addendum after reading this 4-2-14 article:

. . . Excellent article, as expected from you. I’m reading in 2019, and the article has not aged. Here’s a deeper look at the “Wait” vs. “Take Now” math that you only touched on. I’ll use an example. I’m 64, an ex-exec, was just laid-off from my job and unlikely to get regular salary/income beyond nominal contract work the next few years. $800K in Traditional IRA. No debt. I needed to evaluate if I should spend equivalent IRA monies now for living expenses in lieu of SS, and “Wait” as every analyst seems to advise for my SS to grow from 2.6K/mo. now to 3K/mo at 66, or to 4.0K/mo at 70.

On the surface, Wait might appear to be prudent, but most analysts forget that “you’ve got to live on something.” You have to do the fairly simple spreadsheet modeling to see that the benefits of Take Now far exceed decrementing my IRA for living expenses. My model shows at only 2% IRA growth (e.g. US treasuries) and 2% SS cola, crossover in favor of Wait only occurs at age 88! Assuming 4% IRA growth, it never crosses over. Understood there are tax, RMD, survivor, and spousal variables, but we all should first analyze the underlying math. It’s eye-popping!

Addendum – I see you covered this concept above, but the curves are not what I’m seeing. Consider this: I take SS now at 64 (2.6K/mo) and avoid decrementing my TIRA by that amount ($201K) to age 70.

— At 2% return, TIRA grows to $271K by 85; Wait to 70 is $221K; crossover to Wait is 88

— At 3% return, TIRA grows to $313K by 85; Wait to 70 is $221K; crossover to Wait is 98

— At 4% return, crossover to Wait is beyond age 105 (where my model ended).

At its heart, this is a classic future cash flow alternatives analysis, and I urge everyone to go do the simple spreadsheet math first before factoring all the other variables (or tell me where I’m wrong!). Thanks