Executive Summary

For most of its history, financial planning was compensated through commissions paid on the products that were implemented, or the portfolio that was managed on an ongoing basis, after the initial plan was presented. While unfortunately this framework for financial planning created some conflicts of interest, and limited its reach (to only those who needed a portfolio to be managed or a product to be purchased), it made the pricing of financial planning services rather simple – because the pricing was tied to the existing compensation of existing business models (commissions or AUM).

However, with the ongoing rise of financial planning as a standalone service, so too comes the opportunity to charge standalone financial planning fees, entirely separate from the need to implement financial services products or portfolio management. The good news of this flexibility is that it opens up new segments of consumers to receive financial planning. The bad news is that there’s virtually no existing framework for financial advisors to determine how much they should charge in a world where they can potentially try to charge “anything” they want.

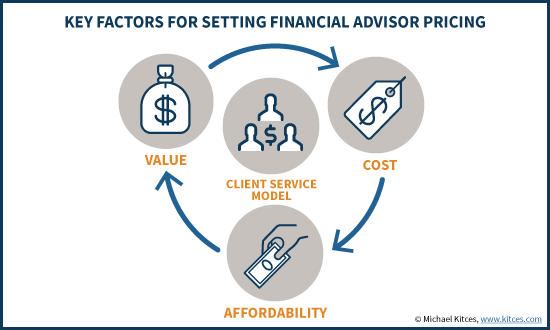

Of course, in the end a financial planning business is only viable if it correctly offers a service that consumers value, can afford, and that can be delivered profitably given its costs. Yet in the context of financial planning fees, each of those mechanisms – the cost (in terms of time) to deliver the service, its affordability for clients, and its perceive value – are each mechanisms that can be used to set a price on financial planning.

For instance, some financial planners might set their pricing based on the cost of their time; financial planning services that take 10 hours per year to deliver, where the financial advisor cost of time is $150/hour, would be a $1,500/year (or $125/month) service. Alternatively, clients might pay based on what they can “afford” to pay, such as a retainer pricing formula based on 1% of income, or 0.5% of net worth (or 1% of investable assets). Or financial planners can price their services based on the perceived value to the client; after all, if high-income clients value their time at $1,000/hour, then they may be willing to pay anything up to that hourly rate, regardless of the cost of the financial planner’s time directly, because that’s what it is worth to the client.

Of course, in the end, setting a proper pricing structure for financial planning services also requires identifying a clear target clientele who will receive the service, to ensure the proper fit of relevant services, with a high perceived value, an affordable cost, that the financial advisor can deliver profitably. Still, even once a target clientele has been identified, the cost of a financial advisor’s time, the value of the financial planning services, and the client’s ability to afford them, are all relevant mechanisms for setting a proper price on financial planning.

Flexible Pricing With Fee-For-Service Financial Planning

The reality for most of the history of financial planning is that as financial advisors, we did not get to set our own pricing. Instead, the consumer cost for our services was determined by the pre-determined commission schedules of the products we sold. At best, the advisor decided which products to sell – and whether or how much financial planning to provide along the way – but the amount of compensation received for implementing a strategy was simply based on the commission payouts for the products the consumer purchased or otherwise invested in to.

Over the past 15 years or so, the rapid ascent of the Assets Under Management (AUM) model provided somewhat more flexibility, as while some advisors simply generated “AUM fees” from 12(b)-1 fee trails on mutual funds, an increasing number had the flexibility to set their own management fee (whether for discretionary management or a fee-based wrap account). Still, though, with a popular “1%-of-AUM” industry rule of thumb on pricing, the price range for a financial advisor was still somewhat limited… in part because services were only rendered for those who had substantial assets to manage in the first place. And it’s still up to the financial planner to decide whether or how much financial planning to actually do on top of just managing the portfolio itself.

By contrast, with the ongoing rise of fee-for-service financial planning – where consumers don’t purchase products or pay for portfolio management, and instead pay for the financial advice itself – there is far more flexibility for financial advisors to set their own pricing, and decide exactly what financial planning services will be delivered for that cost. This makes it feasible to accommodate a wider range of clientele than the AUM or product-centric models permitted, and creates opportunities to be compensated for a wider range of financial planning services.

[Tweet “The rise of financial planning makes it more challenging for advisors to set fees appropriately.”]

The downside, however, is that deciding what financial planning services to deliver, and what to charge for it, is actually such an open-ended opportunity, that it can be challenging for financial advisors to determine their own pricing, finding the balancing point between what the advisor can deliver profitably, what clients will value (and pay for), and how much the advisor must charge for it to be profitable.

In other words, for any particular financial planning service model the advisor might deliver to clients, the pricing model is a balance of three elements: what can clients pay (affordability), what is it worth to them (value), and can the advisor make money doing it (cost).

And in fact, each of these key levers – cost, affordability, and value – can be used to set the appropriate financial planning fee.

Pricing Financial Planning By Financial Advisor Cost (Of Time)

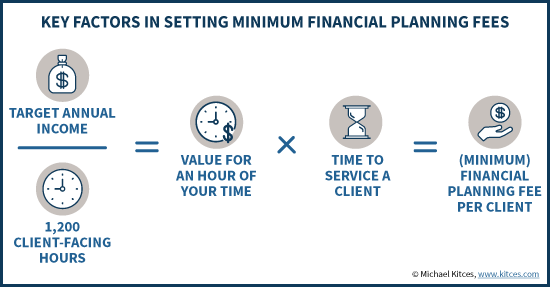

A financial advisor’s clients pay for expert advice. And while some experts have more expertise and skill than others, ultimately all advisors are constrained by their available time. There are just only so many hours in the day (or week, or month, or year) to service clients and provide them advice. Which means in essence, financial advisors who are in the business of getting paid for their advice are selling access to their time as an expert.

Accordingly, like many fee-for-service professionals, one of the most straightforward ways for a financial advisor to price his/her services is to set a price on time. The approach is akin to the “cost-plus” pricing model using in many industries – where the price of the product or service is based on the cost to provide it, plus a margin for profit – though for many financial advisors, the reality is that the overwhelming portion of the “cost”, along with the “plus” and opportunity for profit, simply is the selling of the financial advisor’s time.

For instance, if you’ve determined that providing all the client deliverables on your annual financial planning service calendar – including meeting twice per year, in-between check-in calls, answering client emails, and other support services – will take 10 hours per year, and you value your time as a professional at $150/hour, then you need to charge at least $1,500/year for your services.

Notably, how you generate that $1,500/year of client revenue may vary by the business model. Perhaps the advisor will still utilize an AUM model, and simply have a $150,000 asset minimum (at a 1% AUM fee). Or the advisor could simply charge a $1,500/year annual retainer, or break it into a monthly retainer of $125/month instead.

Regardless of how the fee is billed, though, the driving two factors in setting that $1,500/year fee would be the anticipated 10 hours/year of service work for clients, and the advisor’s targeted value for those hours of time. In turn, the former would be determined by establishing a client service calendar of all the services that will be provided to the client throughout the year (to add up the hours it will take), and the latter can be determined simply by taking a target income level and dividing it by either 2,000 hours (roughly the number of working hours in a year), or perhaps by 1,200 hours (the number of realistic client-facing “billable” hours given the other non-client-facing business obligations a financial advisor has). For instance, if the advisor’s goal was to earn $120,000/year, he/she had better charge at least $100/hour for those 1,200 hours of client-facing time; if the goal is to earn $250,000/year, the hourly rate would be $208/hour. (Though be certain to also allow for additional overhead costs to reach the net income you want!)

Notably, for many advisors the greatest challenge in setting pricing based on the financial advisor cost of time is the ‘uncertainty’ in how much time it will take to service each client. The wider the range of clients – i.e., the less focused and niche-oriented the advisory firm – the more difficult this will be. Conversely, advisors who focus clearly on a specific niche clientele, and formulate a service model customized precisely for them, will have the most consistency in time-to-service, and therefore can price the most effectively. Otherwise, advisors are forced to determine some form of “complexity-based” pricing model, which attempts to determine the requisite number of hours to service the client’s needs based on how “complex” their situation is.

Charging Financial Planner Fees Based On Affordability

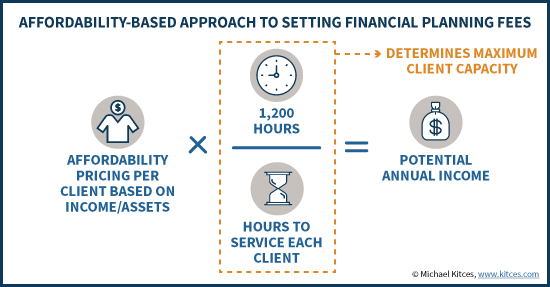

The preceding financial planning pricing model was based on setting a value for the financial advisor’s time, figuring out how much time it would take to service clients, and then setting a total (annual) fee accordingly. However, the risk of this approach in the abstract is that the advisor may unwittingly end out offering a service at a cost that is not affordable to the target clientele in the first place. Not that the service wouldn’t necessarily be valuable… but there’s a level of “deluxe” service that may be entirely valuable yet sheerly affordable for most.

Accordingly, an alternative approach to establishing pricing as a financial advisor is to set costs directly based on what the client can afford, and then determine/create the services that will be provided (in a cost-effective and profitable manner) to justify the cost.

In point of fact, this is essentially how the AUM model works now. With pricing set as a percentage of the portfolio, the cost of the advisor’s services scale naturally to the size of the assets, ensuring affordability. A $1,000,000 portfolio pays $10,000 and a $3,000,000 portfolio pays $30,000, because a 1% AUM fee naturally increases the fee based on the size of the portfolio that would be paying the fee. The larger portfolios pays more in part because the larger portfolio can afford to pay more.

On the other hand, some advisors have been increasingly experimenting with affordability-driven pricing models that aren’t based directly on the size of the portfolio alone. For instance, The Planner Center of Moline, IL uses a model of charging 0.50% of net worth plus 1% of the client’s income to set their financial planning retainer fees. And we’ve found that several financial advisors in XY Planning Network have begun to set their retainer fees at a level that approximates 1% to 2% of the client’s annual income.

Notably, affordability-based pricing is not just a free pass to charge people with higher income or assets (or net worth) a higher fee. It’s still essential for the financial advisor to deliver a relevant and valuable advice service to the client at that price point, or else clients may not sign up, and/or will terminate soon there. In addition, because of the financial advisor’s cost-of-time constraint, it’s still necessary to ensure that the services being offered relative to the total price still allow the advisor to be paid appropriately for his/her time.

Of course, as noted earlier, the reality is that even for a financial advisor who prices based on time, it’s still necessary to affirm that the service being offered is affordable to the client, or no one will buy. Nonetheless, there’s still a fundamental difference between pricing based on time and trying to ensure it’s an affordable service, versus having a pricing model that is literally based on a “formulaic” determination of what would be affordable to the client (e.g., 1% of assets, or 1% of income, or 0.5% of net worth, etc.) and then trying to ensure that the services being delivered to validate that financial planning fee can be provided in a cost-effective manner.

Value-Based Pricing To Set Financial Planning Fees

For both of the prior methodologies, pricing was based on the financial advisor’s cost of time (or at least what he/she thought it should be worth), or what the client could afford to pay, but the pricing wasn’t actually based directly on the perceived value to the client. Obviously, if clients don’t perceive value in the service at all, they won’t pay at all (regardless of the price), but once again the fact that the service must be valuable is different than actually setting the pricing itself based on the perceived value.

In a wide range of other industries, this “value-based pricing” approach has become increasingly popular in recent years. The fact that the value of something may be perceived as higher than its raw costs are why brand-name drugs cost more than generic drugs, and why Apple can sell a smartphone for about $600 when you can get a basic smartphone that has substantively similar features – call people, surf the internet – for 1/3rd that price or less.

Value-based pricing has also become more popular in many service industries. It’s the lawyer who sets their legal fees based on the anticipated size of the lawsuit or settlement. Or the accountant who prices their tax strategies based on a percentage of the tax savings that will be generated.

The challenge of value-based pricing, though, is that perceptions can be both hard to measure at the best, and fickle at the worst. Which means it’s especially important to have a clearly defined niche and a specific service that you provide to that niche, in order to establish a (premium) perceived value for it.

In point of fact, the AUM model – for those who actually offer an investment management service that is perceived to have the potential to create alpha – is a version of value-based pricing. Not only because people can/do pay more for an active manager than a passive one, but are also willing to pay 3X the fee on a $3M portfolio than they do on a $1M portfolio (because at that point the investment manager is providing the value for all $3M instead of just $1M!).

For a financial planner, one of the most straightforward mechanisms for value-based pricing is to look at the value of time for the client. In other words, the question is not what is the advisor’s time worth to provide the service, but what is the value to the client to not take the time to do it themselves? In this context, the higher the client values their time, the greater the perceived value of the service. Which means for clients who value time even higher than the advisor does, a natural value opportunity (and higher pricing potential) emerges.

For instance, imagine working with senior executives or business owners who value their time at $1,000/hour. With such clients, an advisor who “just” charges $500/hour would be perceived as a huge value for the client (a 50% cost savings for their own time), even if that price is 3x what the financial advisor would have billed out based on their own cost of time. And notably, such a value-of-time discrepancy isn’t just solely the domain of ultra-high-income people whose time is literally priced that high; it can also occur for those clients who simply place their own high premium value on their personal time (because they have a strong preference to do family, personal, or other activities with their time instead).

Notably, this approach does once again require having a highly focused service for a relevant target clientele, both because it won’t work unless it really is offered exclusively to those who actually do value their time so highly. And also because it’s still possible for the advisor to deleverage the value of their own time if it really does take them “too long” to provide their services; in other words, the client may value their time at $300/hour, but if it takes the advisor 3 hours to do what the client could have done themselves in one hour (and charges accordingly), everyone still loses.

Nonetheless, arguably a value-based pricing approach is the potential path to drastically higher financial planning fees than any other pricing model, because it creates pricing and value opportunities that go beyond just determining the price based on financial advisor costs or client affordability alone.

In the end, the reality is that any form of financial advisor pricing model must still bring together the key elements of a service that the client can afford, the client will value, and that the advisor can deliver profitably given his/her cost of time (and any other business/overhead costs). And it will be difficult to refine any pricing model for financial planning fees if the advisor doesn’t have a clear understanding of who the target clientele is in the first place, as that’s essential to understand what the client can afford, what the client would value, and what services the financial advisor must deliver (and the time it takes to do so).

Nonetheless, the details of how pricing is ultimately determined – and communicated to the client – can still be built around any of the three pillars of cost, affordability, and value, and each may be relevant for different types of clientele, and will lead to different conversations with the client about the cost of the advisor’s financial advice.

So what do you think? How did you determine the pricing for your financial planning services? Are you considering a change to your pricing based on any of these approaches? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Good read. Had a talk with a prospective solo planner just yesterday and told him he needs to square away both his pricing schedule and his purpose for that schedule as one of his main priorities. So this is timely as I’ll forward this on to him. Thanks Michael!

…and since you asked at the end how readers set their pricing. I set mine up with affordability in mind, tying pricing directly to the net worth of the client. Afterall, my lower tier clients don’t take a ton of time to service (so not a huge time-cost to me) and I feel good as I know without a pricing schedule like mine they probably would never engage a planner. If interested: Thinkingwealth.com.

Good morning Michael,

I’d like to get your opinion on the “affordability” portion of Financial Planning as I have a pipe-dream idea that revolves around this. As you’re well aware, quality financial planning can be difficult to gain access to for people with less means. I hate that and wish there were more options. Here’s my pipe dream to help:

– Financial Planning non-profit organization that charges on a “pay what you want” basis (similar to humble bundles if you are familiar) hopefully filling in gaps in budget through grants/donations or some sort of partnership with a university

– Provides planning to any and all clients, no matter the size (potentially making referrals for special cases)

– Partnership with local university could provide FP students for some cases to provide them experience (similar to Texas Tech’s Red to Black program)

This is essentially my semi-retirement dream. I’d pay myself $10-15k a year in salary, work 10-20 hours a week, and hopefully the program would be autonomous while I’m not there. In the mean time, many in my community could get quality planning services for whatever price they deem fit. There’s probably some huge hurdle I’m missing, but what do you think?

Thanks

Barney,

The blocking point is that regarding of whether you’re a for-profit or non-profit, the challenge is getting a critical mass of clients (to pay anything at all).

It’s actually not “hard” at all to charge $60 – $80/hour for financial planning services (less than half the “typical” hourly rate), if the issue is just “what can you charge to be profitable”.

The failure point is getting a sufficient volume of clients to pay that rate so the math works out. People don’t show up for free just because the planning is cheaper. In fact, sometimes that makes them distrust it even more (when it feels “too inexpensive” relative to the alternatives).

See https://qa.kitces.com/blog/the-real-reason-that-financial-planners-fail-to-serve-the-majority-of-americans/ and also https://qa.kitces.com/blog/the-real-hidden-cost-that-has-been-inhibiting-financial-planning-for-the-masses/

– Michael

Hello. Very nice article of wonderful thought provoking material.

Investment management and financial planning are two completely unique services that have little to do with each other from a support structure, expertise, risk, and cost standpoint. They have completely different risk characteristics and costs to provide. They should be priced and provided separately. An advisor should be responsible to know what it costs to provide their investment management services (including risk cost, expertise cost, and profit margin) and thereby pass on an appropriate fee to their clients. Same thing goes for their financial planning services. They are completely different services, they should (each) be charged accordingly.

Thanks for the article Michael, and thanks for this comment TMPG. I’d like to move to a primarily fee-centered business model, yet I’ve been pondering what the best business model is. To your comment, I’ve been considering doing the financial planning for a fee, then implementing (fee-based asset management, insurance, so on) which jives more with your comment here. Is this along the lines of what you were saying? Thoughts on that?

One element you may have omitted is mine. First, I am a customer not a financial planner. We selected our fee only money manager 15 years ago. I felt uncertain about making investment decisions. The firm we chose offered access to DFA funds, which I liked. Now I am retired and wonder about co to Hong to pay 75 basis points versus selecting a similar portfolio through Vanguard or Fidelity. While some of the DFA funds could outperform the index or ETF funds I might select, I have a margin of downside. Or, stay put cuz it’s working. How should I decide?

Chris,

Mainly, you should decide by putting a value on all the other advice, planning and services (beside investment advice) you are receiving and will likely be receiving in the future from your planner. And determine whether you are getting your money’s worth.

I am a little confused by your assumptions in the scenario where you base prices on the financial advisor cost, i.e. you need/want to make $120k so charge $100/hour times 1,200 hours of billable time. What about the ever increasing cost of overhead? Are you assuming here that these planning hours are an add on to money management fees which cover your overhead?

RBF,

Sorry for the confusion.

Indeed, you’ll need to add more to the pricing (or more hours to the work) to cover overhead.

Given that overhead varies RADICALLY for firms – some that run with <$10k of total costs, and others with 3x or 5x that – the impact will vary a lot. But I've added a note to the text to at least clarify that SOME allowance for overhead should definitely be there…

– Michael

Michael,

The only thing missing is compensation to the firm for client value created by virtue of investment in technology as opposed to the advisor’s time. Which is the whole point of trying to robo-ize part of the deliverable. Simple example; moving from printing, reviewing and mailing or emailing reports to push of a button delivery of reports to a client portal reduces the advisor’s time input to this deliverable but doesn’t diminish the value to the client. Now of course this opens the firm up to pure robo competition – at least for this part of the service. But lots of clients may be willing to pay 35bps for investment advice from the same firm that’s providing excellent wealth management services (either for additional AUM bps or a separate retainer) rather than move to a robo at 25 bps or to do it themselves.

Just an FYI,

Accountants cant really charge contingent fees anymore… i.e. a percentage of tax savings generated. I’m pretty sure its the IRS that will come down on them since the tax shelter department controversies of the 1990s and early 2000s. Examples included KPMG’s tax innovations group that specialized in building beautifully elaborate tax shelters worth $10s of millions to various clients and companies and selling the ideas and implementation for a few million (or a decent percentage of the tax savings).

Eventually, there were investigations and contingent fees in tax accounting are now heavily frowned upon. It’s either the IRS that will hit for you it today or maybe the AICPA, but either way I’ve talked to a few accountants who lament that they can’t do contingent fees.