Executive Summary

One of the fundamental principles of long-term investing is the recognition that, while markets may go up and down and be volatile in the short-term, eventually the volatility tends to average out into favorable long-term growth rates. Accordingly, the conventional wisdom in the face of market volatility is simply to keep invested and stay the course. Of course, those who are approaching or transitioning into retirement need to be cognizant not to draw down the portfolio too much waiting for those returns to average out – a phenomenon known as sequence of return risk – but as long as investors stay a little flexible on their retirement goals, and spend reasonably conservatively, that sequence of return risk can generally be managed.

However, the fact that investors will for the most part simply have to accept whatever returns the market gives – and in whatever sequence it provides them – means that different generations of investors may have substantively different experiences with long-term investing simply based on whatever happens to occur during their particular investment sequence and the "investment cards" they're dealt.

In turn, this effect is further amplified by the fact that early investment experiences often shape a lifetime of investment behavior – from Baby Boomers that experienced favorable market returns coinciding with the rise of the 401(k) and have stuck with markets during their difficult years, to late Gen X’ers and Millennials who have had to wait as much as a decade or more simply to see the markets recover to where they started when they first begin investing (hearkening back to the experience of a Lost Generation of investors after the Great Depression who never returned to stocks after the scarring experience of the crash of 1929 and its slow recovery during the Great Depression). And in fact, a growing volume of data on investor behavior is suggesting that younger investors are indeed far more skeptical of stock markets and long-term investing… a challenge that may not necessarily reverse itself even as the market improves (just as the bull market of the 1950s and 60s didn’t necessarily win back Depression-era investors).

The fact that the generational timing of young adulthood – and the market returns that coincide with it – may have such a long-term behavioral influence notably also extends to financial advisors themselves, as Baby Boomer advisors in their early 60s today saw a raging bull market for the first 20 years of building their careers, while younger Gen X and older Millennial advisors have had to wait 10-15 years just to see the markets recover to where they invested their first clients! Which raises the question of whether advisor attitudes about the value of providing investment management, and the active vs. passive debate, may also be heavily shaped by the advisor’s generational experience and the timing of when they happened to launch their advisor career?

Ultimately, though, the key point is simply to recognize that mere birth year may actually be responsible for a far more outsized portion of our lifetime investment behavior and experience than is commonly acknowledged. As even if a long-term portfolio can mathematically recover from almost any sequence of returns, it doesn’t mean that certain generations of investors – and advisors – will behaviorally do so themselves, based on whatever early-years' experience the market happens to give them during their formative years?

The Impact Of Return Sequencing On Savings And Investment Behavior

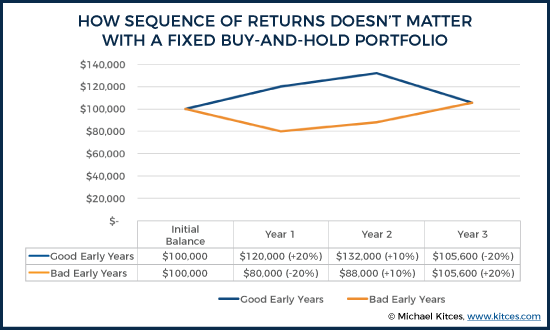

The commutative property of multiplication means that the result of multiplying several numbers together is the same regardless of the order in which the multiplication occurs. Thus why 3 x 5 x 10 (which simplifies to 15 x 10 = 150) is the same value as 10 x 5 x 3 (which simplifies to 50 x 3 = 150).

And the same is true when it comes to investment returns; a sequence of +20%, +10%, and -20% produces the same 5.6% cumulative growth rate and final net worth as -20%, +10%, and +20% (technically the multiplicative product of 1.2 x 1.1 x 0.8 = 1.056). In other words, in investing it doesn’t matter whether the good returns come at the beginning or the end, the final result is the same.

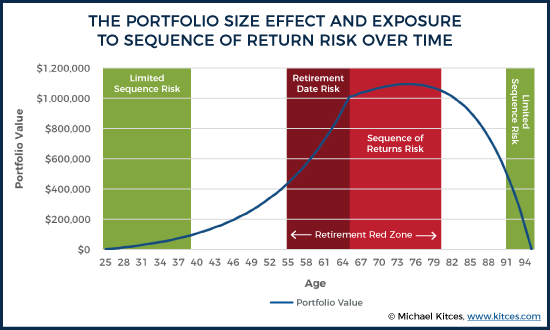

However, this commutative property of multiplication only holds when each step (each return) is weighted equally. Which means that once cash flows occur in or out of the portfolio – e.g., for those making ongoing contributions or taking ongoing distributions – a “sequence of returns” risk emerges when calculating the real-world dollar-weighted return. Because a retiree taking ongoing withdrawals who gets bad returns early on might actually run out of money before the good returns show up to average out in the long run. And similarly, an accumulator who’s still saving isn’t adversely impacted by a bear market in the early years – when there isn’t much saved up yet anyway – but can be very adversely impacted by a market decline in the final decade leading up to retirement.

Because the reality is that it’s in that “retirement red zone” of danger – the decade leading up to retirement and through the first 10-15 years of retirement itself – when the size of the portfolio itself is the largest, and most sizably impacted by an ill-timed market decline. By contrast, bear markets are less problematic in the later years of retirement (because there isn’t much time horizon left to grow anyway), nor is a bear market as impactful at the beginning of a young saver’s journey (because the reality is that in the early years, whether and how much is saved has far more impact than the growth on that still-small account balance).

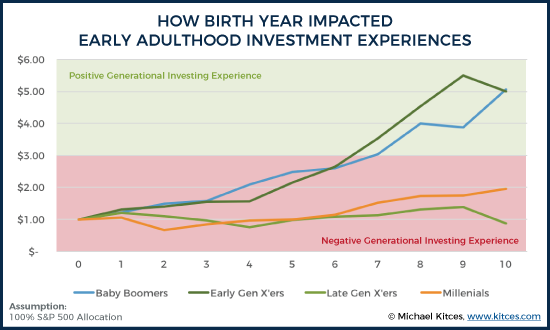

However, the mathematics of saving and investing for retirement are not the same as the psychological experience of doing so. In particular, younger savers who are learning and experiencing investing for the first time – and have a bad investment experience – may potentially be scarred to the point of not wanting to invest at all in the future. After all, despite the tremendous stock market gains of the 1950s and 1960s after World War II, a large slice of Americans who came of age during the Great Depression never participated, having experienced the early scars of market losses (either via the general media, through their own investing, or from family and acquaintances).

And now researchers are finding that Millennials may similarly become another “Lost Generation” with lagging wealth accumulation due to the ill-timed financial crisis that struck in their early formative years. In other words, mathematically speaking, those who experience good market returns need to invest less for retirement (because their assets are literally growing more) while those who experience bad returns need to save more to catch up; but in reality, those who experience good returns in their early years tend to save more, feeling rewarded for their good savings behavior, while those who experience bad returns save less or abandon investing altogether rather than just saving more to catch up!

The (Generational) Path Dependency Of Wealth Creation

The reason why the impact of return sequencing is so important when considering the trajectory of savings, investing, and wealth creation, is that the biggest driver of return sequencing is simply the returns of the market itself, which is beyond the control of any individual investor. Certainly “bad” investing behavior and poor market timing can make the results worse, but most of the uncertainty is driven by the volatility and unknown sequence of returns that will be delivered by the market itself. Which means when someone happens to begin saving and investing – merely as a result of when they happen to enter adulthood and become able to start saving and investing – can have a surprisingly large impact on the trajectory of wealth creation.

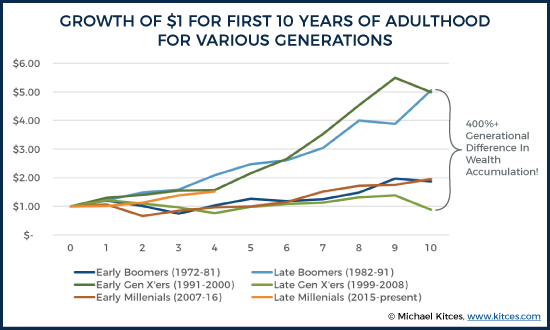

For instance, consider the relative paths of the various current generations of investors. According to standard demographic dividing lines, current generations of investors include Baby Boomers (born 1946 to 1964), Gen X’ers (born 1965 to 1980), and Millennials (born 1981 to 1997). (The subsequent Gen Z’ers are still in school and haven’t quite yet begun to graduate from college and enter the workforce.) Yet while these generations currently span different stages on the path of accumulating for retirement – with Baby Boomers already in retirement or transitioning imminently, Gen X’ers in their peak family stages (late 30s to early 50s), and Millennials still starting their careers and families (early 20s to late 30s) – they all started in the stage of early adulthood saving at some point. And as it turns out, at very different starting points.

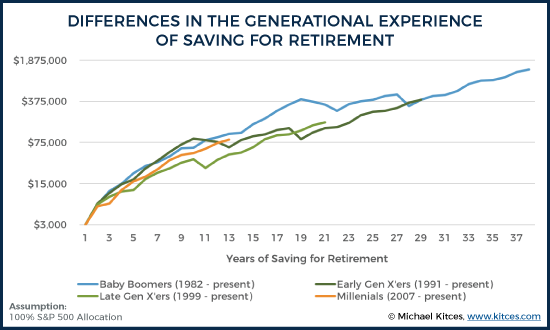

Specifically, the chart below shows the path of wealth over the first 10 years of early adulthood (from ages 22 to 32) for the various generations (and since most generations are 15-20 years wide, broken into early/late sub-groups to better separate out their relative early-investing experiences).

As the results clearly show, there is a material difference in market trajectories during the formative young adult years from one generation to the next. Of course, the reality is that for early Baby Boomers in the 1970s, stock market investing wasn’t as common as a savings path for retirement, as the IRA had only just been created in 1974 (with a mere $1,500 contribution limit at the time), and the capability to offer a 401(k) plan wasn’t added to the Internal Revenue Code until 1978 (and wasn’t being implemented in corporate America until 1982, after the IRS issued Regulations in 1981). Thus, in practice, most early Baby Boomers started saving for retirement accounts at the same time as later Boomers.

The significance of this timing is that in practice, there are really two sub-sets of generational investors, with drastically different early investment experiences – Baby Boomers who started in the 1980s along with early Gen X'ers who started in the 1990s and have a great early experience, as contrasted late Gen X'ers and early Millennials who started in the years leading up to the tech crash and financial crisis and had a terrible first decade to be investors. (While late Millennials have only just begun to save, which means it’s too soon to tell.)

Of course, as noted earlier, the reality is that in the long-term, those saving for retirement are mathematically more impacted by market volatility in the later years than the early years. Nonetheless, the initial trajectory of saving and accumulating has a substantial impact on the overall “path” that investors follow over their entire lifetime.

The effect is further amplified by the fact that when the future isn’t ultimately known, we human beings still have a tendency to project the (recent) past instead. Which means for Baby Boomers who ultimately experienced difficult markets in the final decade leading up to retirement – potentially delaying their intended retirement date – by the time they got there, they already have very positive feelings and views towards markets and investing and a "faith" that any market hiccups would recover soon (thanks to all that had already been created). Whereas for younger generations, their only experience with investing has been largely negative, which means even if it ultimately works out in the long run with better future returns that average out… for the time being, the outlook is just depressing relative to prior generations!

As the chart above shows, assuming an ongoing savings of $250/month for an early accumulator ($3,000/year), the different generations have experienced a substantially different trajectory in pursuing retirement savings, with Baby Boomers pull ahead from the start and then rocketing further ahead in the second decade of accumulating, while early X’ers had a good start but faltered mid-way and are just barely catching up, and late Gen X’ers and Millennials are still struggling to even get going and are already behind.

Of course, the reality is that better future market returns for late Gen X’ers and Millennials may eventually help them to average out to the same long-term return as Boomers. But thus far, their experience is that Baby Boomers and early Gen X’ers had a great start, and are simply hoping to revert back to more of the great returns from their earlier years… while late Gen X’ers and Millennials have spent the entirety of their formative years experiencing largely negative and sideways markets.

In fact, this timing phenomenon may help to explain why Gen X’ers were so readily eager to abandon investing in markets to pursue real estate in the 2000s (which, alas, didn’t turn out well for them, as X’ers the largest decline in home equity during the financial crisis!), and similarly why Millennials have been so apt to adopt investing in alternatives like Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies (which, again, unfortunately, hasn’t turned out well for them lately!).

Implications For Generational Investors (And Advisors)

The paradoxical effect that bad investment returns should (mathematically) make investors want and need to save more for retirement, but behaviorally tends to discourage investing (because saving feels less rewarding when returns are bad) can create significant challenges to actually helping savers accumulate towards retirement.

For instance, a recent survey from MFS found that Millennials are the least interested in investing in the stock market (with a whopping 46% stating that they would “never” be comfortable investing in stocks!) despite otherwise being optimistic about the economy, and similarly a recent Harris poll found that 80% of Millennials are not currently investing in the stock market (though for nearly half, it’s simply because they stated they can’t afford to do so).

The implication of this from the behavioral perspective is that, at best, young adults may need to be introduced to markets and investing more gradually – rather than the “traditional” approach of assuming they should be invested the most aggressively thanks to their longer time horizon, without any regard to the behavioral impact that may occur if the market delivers poor returns in the early years. In other words, just because young investors can afford (by virtue of their time horizon) to take risks doesn’t mean that they should, especially if it risks scarring their investment behavior for life based on factors entirely out of control (whatever returns happen to be served up by the market in their particular early savings years).

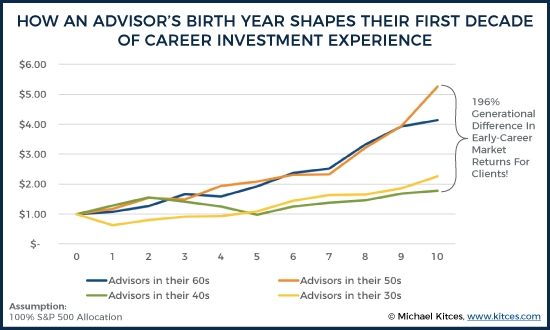

And notably, financial advisors themselves are not necessarily immune to these behavioral effects of how stock market returns are experienced during their early formative years as a professional. As a late Gen X’er myself, it took 13 years for the S&P 500 to reach the levels it was when I started my career, and nearly 16 years for the Nasdaq to recover. If you’ve recommended investments to clients for over a decade and the prices are still lower now than they were with your first client, it’s hard not to be influenced by that in considering either recommendations of how much clients should save, how aggressive they should be, or the best investment approach to achieve long-term returns (i.e., the active vs. passive debate).

Accordingly, another way to look at the earlier age-based (generation-based) pathways for investors is to reflect on the pathways that advisors have experienced in their own careers, and how it may shape the advisor’s own attitudes about investing. For instance, a Baby Boomer advisor today in their early 60s would have started their advisor career in the late 1970s, where after a brief initial hiccup, the markets largely went straight up for the better part of 20 years (during which they built the bulk of their career and client base), and advisors in their 50s still enjoyed at least a decade of positive returns (starting in the late 1980s), but those in their 40s got only a few years of good returns before the tech crash, and advisors in their 30s similarly started in the face of the financial crisis.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that our experiences in our early adulthood can shape our attitudes for the rest of our lives – including (and especially) when it comes to our experiences with investing. Except as it turns out, the biggest determinant of our early adulthood investment experiences is simply “what the market delivers,” which occurs almost entirely beyond the control of the individual investor. And the fact that everyone at a similar age/stage experiences substantively similar market returns – whatever the market provides – means that certain generational groups and cohorts of both investors and advisors can end up with substantively different views on markets and investing simply by virtue of their birth year and however it happened to line up to the bull and bear cycles of the market.

Or stated more simply – is the mere year in which we happened to be born actually responsible for a far more outsized portion of our lifetime investment behavior and experience than is commonly acknowledged?

So what do you think? Do different age cohorts and generations really treat investing differently based on their early adulthood investment experiences? Should this influence the way we think about investing (and especially introducing investing to younger investors in early adulthood)?

Leave a Reply